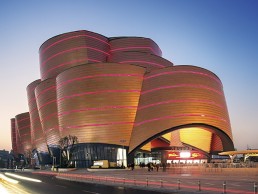

Movie Theme Park, China

Developed in conjunction with Dalian Wanda Group, the Wuhan Movie theme park is the creation of London-based Stufish Entertainment Architects. Having started on the project in 2010, Fisher sadly passed away in 2013 just eighteen months before the project’s completion and as such, the Wuhan Movie theme park was left in the capable hands of the Stufish team to carry out to fruition.

The Wuhan Movie theme park is a $690m project that sees the world’s first entirely indoor theme park stacked with dynamic attractions over multiple storeys. Using over 10,000 bespoke geometric golden aluminium panels, the building’s façade is lit in its entirety with linear LED channels that are fastened behind said panels in every 100mm gap of the 700m tall façade.

Nicknamed ‘The Golden Bells’, based on the 2,000-year-old local symbol of the bronze musical bells ‘Bianzhong of the Marquis Yi of Zeng’, Stufish architect Maciej Woroniecki told mondo*arc of the project’s beginnings: “We were approached by Wanda to propose a concept for the Movie theme park during the design phase of the Han Show theatre. The initial brief called for an iconic design that would reference symbols of Hubei province, while also push to express the nature of the content of the theme park movies.”

The façade of the Wanda Movie Park is set 300mm proud of a standing seam surface. This gap, according to Woroniecki, was utilised as a diffuser and lit in order to create a low resolution screen along the entire façade surface. “As there are 50mm gaps between every golden façade panel, there exists enough resolution to run live content along the façade to support both the internal attractions and the geometry of the façade itself, through a variety of different animations,” said Woroniecki.

The theme park’s original lighting scheme focused much more on amplifying the building’s form rather than animated content. According to Woroniecki, the one drawback from playing live content on the façade at night is the reduction in contrast between the physical façade volumes, as the delineations of the façade begin to blend separate surfaces into one another.

“One of the biggest challenges was securing a consistency in the spread and orientation of lighting between each housing,” said Woroniecki, “as any slight deviation from the required orientation would have become incredibly apparent from ground level.”

As the building is a movie inspired theme park that contained animated visuals, it was imperative the lighting reflected its purpose and so it was only appropriate that it was animated at night and while the resolution of the lighting is not able to directly represent the different content of the attractions, it promotes the general presence of an indoor theme park.

Summing up the Stufish experience, Woroniecki continued: “Unfortunately the requirements of the programme and the restrictions of the site dictated how expansive the building could be – in how far the façade could push away from where it met the ground.

“Had the site restrictions been less, moving the volumes apart to create indoor / outdoor spaces would have benefited the general layout and overflow areas. If the volumes could have shifted further apart from one another there would have been more potential for larger variations in the sizes of the façade forms – creating a much more striking and dynamic architectural proposal.