Technology Centre, Minden, Germany

To create a flexible, easily changeable lighting scheme, Teamlicht used motorised spotlights from ON Lichttechnik at Minden’s new Technology Centre.

Working alongside architectural office Dälken, lighting designers at Teamlicht have created a bright and airy environment for a new Technology Centre in Minden, Germany.

The entire complex was designed to be a modern, innovative workspace, and the lighting contributes to this greatly thanks to a flexible scheme that utilises motorised spotlights from ON Lichttechnik.

The interior design of the main atrium space is based on a fluid concept, with changing exhibitions from Follman Chemie and Triflex – companies that use the workspace. However, the vast height of the space meant that the lighting wasn’t as straightforward as first hoped.

“For our work, this meant that we had to develop a concept that can adjust to the various lighting requirements with minimal effort,” said Teamlicht. “Having this in mind, the idea came up to use motorised spotlights by ON Lichttechnik that can be controlled easily through wall panels. The spotlights are rotatable and tiltable, and can further change their beam angle.”

Complementing the artificial lighting, the architecture is characterised by abundant daylight, thanks to a glass façade that connects the interior with the exterior. As such, the lighting for both the interior and exterior was coordinated through an intelligent control system. A shading system was integrated into the control system. An example of this comes through pre-programmed lighting scenes in the auditorium – not only are spotlights directed and changed in brightness depending on the scene, but the shades move up and down based on the chosen scene.

The auditorium space can be split through a separating wall into three different sizes, making it suitable for meetings, training and other events. Here, the motorised spotlights are supported by recessed downlighting, with decorative pendants and indirect lighting adding a soft finish.

Looking back on the project, Teamlicht are satisfied with the success of the lighting scheme. “We were surprised how well our plan worked out. Through different lighting scenes, various room atmospheres were created. The auditorium is a good example of this: the lighting scene with a uniform and bright lighting allows for an active and concentrated training, while a dimmed down, high contrast lighting suits for an evening event,” said the designers.

“The usage of motorised spotlights was new for us, and is also the standout feature of the project. It makes the usage of the interior far more flexible.

“As a lighting designer, we have to take on the task of achieving targeted, atmospheric, efficient, and economical solutions for the project owner. The solution with the motorised spotlights showed us how comfortably and easily the lighting can be changed in a room by pressing one button.”

www.on-lichttechnik.de

www.teamlicht.de

Fishmongers' Hall, London, UK

A Scheduled Ancient Monument on the banks of the River Thames, Fishmonger’s Hall has been given a dramatic new lighting scheme by Light Perceptions. The designers used Lutron controls to bring the scheme to life.

Fishmongers’ Hall is the home of the Fishmongers’ Company, one of the oldest and most ancient Livery Companies of the City of London. The Hall itself is a Scheduled Ancient Monument, and a significant testament to the development of commercial activity and trade regulation in the City of London. The site is a fine example of an early 19th century livery hall, is Greek Revival in style and is Grade II* Listed.

In 2019 Light Perceptions was commissioned by the Fishmongers’ Company to carry out a Strategic Review of lighting in the Hall, this followed on from the success of a new lighting installation in the Banqueting Hall carried out in 2018, which utilised a Lutron Quantum system for lighting control.

Key recommendations of the Strategic Review included the extension of the existing Lutron system to manage the lighting in many of the public areas of the Hall and has been gradually implemented over recent years with the wireless technology of Lutron’s VIVE system being used to bring pre-set dimming to the main Entrance Hall, Grand Staircase, Vestibule and the important Court Dining and Drawing Rooms.

Energy saving was a key part of Light Perceptions’ Strategic Review and significant savings have already been achieved by using occupancy sensors as part of the VIVE system to ensure that lighting levels reduced when areas are not occupied. Wireless sensors and controls have been used in many areas to ensure that these significant technical advances can be made without causing damage or intervention into the historic fabric of this important building.

Light Perceptions’ most recent work at Fishmongers was the new external lighting scheme, completed in late 2021. The installation is an important presentation of the Hall in the night-time lit environment. The Hall’s prominent position on London Bridge overlooking the River Thames, makes this one of London’s most prominent and visible external lighting schemes. Here the existing Lutron Quantum system was easily extended to control the new external fixtures, allowing subtle changes in emphasis across the south and east façades, providing manual overrides for special events and timed subtle changes at the end of the evening to comply with planning requirements.

The installation was completed just ahead of Light Perceptions’ 20th Anniversary and is one of the most prestigious and visually significant installations completed by the company in recent years. Bruce Kirk, Director, commented: “Completing the external lighting at Fishmongers on the eve of our 20th birthday was an important occasion for us. We have collaborated on several great projects inside the Hall over the last five years and this is the most visible tribute to a great working relationship.”

As Fishmongers continues to seek further energy savings and consolidation of controls across the building, the Lutron system will be able to be extended and adapted using Lutron’s Enterprise Vue as a central controller to provide the essential flexibility required for new and updated controls and BMS integration.

www.lutron.com/europe

www.lightperceptions.co.uk

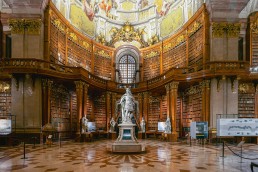

Austrian National Library, Vienna, Austria

Linea Light Group was selected by lighting designers LDA Studio to bring new light to the Austrian National Library in Vienna.

Europe’s largest baroque library, the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (Austrian National Library) is an architectural jewel. Built between 1723 and 1737, the library now holds more than 7 million items; amongst which are 15,000 books that belonged to Prince Eugene of Savoy and one of the world’s largest collections of Martin Luther’s Reformation manuscripts.

The building has an imposing façade with three orders of large windows set on the central pavilion, surmounted by a sculptural group of Minerva on a quadriga. Inside, the grand Baroque staircase leads to the Prunksaal – the Magnificent Hall. Entirely lined with wooden shelving, the library houses statues of personalities from Austrian history and members of the House of Habsburg.

The lighting overhaul project, led by Austrian practice LDA Studio and utilising fixtures from Linea Light Group, involved the hall and access staircase and saw the replacement and restoration of all lighting fixtures and relative electrical components. The aim was to create a more theatrically-lit environment through the installation of high-performance solutions that are perfectly integrated into the architecture of the building; one of the key objectives was to enhance the works while respecting the constraints imposed by historical preservation regulations.

The library’s State Hall extends almost 80-metres in length, with a height of 20-metres. The room is topped by a central dome, frescoed by court painter Daniel Gran in 1730. The previous lighting utilised large floodlights positioned along the gallery, the rendering of which was entirely insufficient. The challenge for LDA Studio was to create a scheme that would ensure exceptional colour rendering and highlight the warmth and colours within the space.

The new lighting system is based on three-phase DALI tracks, on which new LED luminaires are installed and connected. The decision was made to opt for an indirect lighting system, in order to organise the light distribution without compromising the works, but enhancing other details that had previously remained obscured.

LDA opted for various luminaires from Linea Light Group to provide the most comprehensive and respectful lighting possible for the location. Navata Optus projectors were chosen to illuminate the bookshelves, ceiling frescoes and a selection of architectural features. The wall version of the Optus_W2 was also installed, replacing the previous PAR64 fixtures, giving a better result. The two Optus light sources can be individually adjusted, and each luminaire has been customised with a DALI driver for perfect integration into the control system.

With a custom 3500K light colour and DALI control, High Protection luminaires emphasise the historic spiral staircases that lead from the visitor’s floor to the gallery, while Periskop projectors illuminate the statues and busts. A customised version of the Periskop, with 14 narrow beam elements, illuminates the Imperial Staircase.

The end result is a marvellous theatre in which centuries-old works of art and historical artefacts are staged.

The Ivy Asia, London, UK

Showcasing the Asian-inspired interior, lighting designers at 18fifty utilised fixtures from LEDFlex to create a decadent, intimate environment at The Ivy Asia in London’s Mayfair.

Located in the heart of London’s most exclusive neighbourhood, The Ivy Asia is the home to delicious Asian-inspired cuisine, incredible entertainment and lavish cocktails, set within a unique and vibrant décor.

The maximalist décor in The Ivy Asia is just as important to the overall experience as the cuisine. From the illuminated floor crafted from green, semi-precious stone to the cherry blossom trees with twinkling leaves, The Ivy Asia is designed to transport diners to a world beyond their imagination.

Lighting plays an integral part in enhancing this Asian-inspired interior as well as creating a lustrous yet cosy ambience for diners while highlighting focal design details, architecture and artwork for an experience that stuns the senses.

Lighting designer 18fifty specified LEDFlex premium lighting solutions to be integrated within this iconic restaurant chain across London, Guildford, Brighton, and Cardiff.

To set the ambient lighting, coffers in the ceiling throughout the restaurant use Lumen Line in 2300K from LEDFlex’s flagship Flexi Range. To create the golden illumination of the upper wall detail, corridors, and staircases, the 4mm wide Nano Flex HE in 2400K has further been integrated. The luminaire is additionally used to create a warm ambience within the seating booths.

Decadent focal areas of the restaurant such as the bar front, sushi bar, and private dining areas have been downlit using High Lumen Ultimo Neon Silicone in 2200K. As attention is drawn to the front of the bar, the rear is subtly backlit using Nano Flex HE in 2400K. The lighting scheme is also purposefully implemented to draw attention to eye-catching art and mirrors. While Ultimo Neon Silicone SV in 2200K is used to flexibly outline the mirrors, the stunning backlit artwork on the walls is illuminated using Lumen Line in 2300K.

The clever and considered interior design in combination with bespoke LEDFlex lighting solutions met the client’s expectations perfectly, ensuring that these luxury experience dining venues will be ingrained as an unforgettable adventure into the world of Asian inspired cuisine.

www.18fifty.co.uk

www.ledflexgroup.com

LEX Law Firm, Foggia, Italy

The contemporary office space of law firm LEX is complemented by a lighting scheme by Carella+Salvato, which specified fixtures from L&L Luce&Light.

The LEX law firm in Foggia, Italy, regularly welcomes clients in an elegant, contemporary setting where the walls and furnishings are enhanced by a colour palette of pale grey, black and white.

The colours are echoed in the L&L lighting solutions chosen by Carella+Salvato, the designers responsible for the lighting concept. The space is divided into various rooms: the reception area, the office of the practice owner, the meeting room, and rooms for the other team members, arranged along a corridor.

The reception area, where the grey floor creates a visual continuum with the wall, is lit by Stinger 2.0 projectors with built-in power supply, fixed to the ceiling on a track. A striking visual effect has been created by directing the beam of one projector onto the olive tree in the corner of the room – it creates an elegant chiaroscuro image of the foliage on the wall’s grey stone cladding. The same Stinger projectors, this time in version 1.0, have been installed along the corridor. In this case, the fixtures were attached to two tracks on the ceiling, that replicate the bend in the corridor, further emphasising the play of lines in this space.

The office of the law firm’s owner features a wall entirely covered in boiserie and painted black to blend with the room’s furnishings of desk, chairs and filing cabinet. There are six shelves on the panelled wall, divided into two groups of three and separated visually by three light columns, created using small Bitpop C 1.0 ceiling-mounted fixtures with narrow 17° optics and finished in black to match the colour of the wooden panelling.

The lighting design is completed with recessed Brenta linear profiles for the meeting room wall that holds the firm’s law books. The bookcase is made up of 16 compartments arranged in four columns, with the Brenta fixtures installed flush with the surface along the vertical wall dividers in four increasing lengths, creating lines of light that continue from the wall to the ceiling, contributing to the room’s ambient lighting.

JLL Offices, Singapore

Blending a homogenous light with low level, biophilic audio, KScape’s Rail fixtures - linear luminaires fitted with loudspeakers - were used at JLL’s new offices within Singapore’s CapitaSpring building.

To build the next generation of offices, JLL wanted to optimise every aspect of its new 23,500sqft space within Singapore’s CapitaSpring building to create a groundbreaking human centric workplace.

One of the core areas of focus was on noise pollution – a common problem in most open office environments, noise irritation can create a lack of focus, stress, and is harmful for employees over time.

In addition, lighting is an essential component to wellbeing within the workplace. Not only do staff require a light capable of delivering a comfortable performance, but also to work within the wider human centric design, following the light of the day – especially with large windows overlooking the city.

KScape, along with Moodsonic, was chosen by JLL’s design team to reduce office noise pollution. Moodsonic create advanced white noise through biophilic soundscapes created to protect the concentration of the office worker by playing natural sounds at a very low level of 45dB so as not to distract them, but also to mask unwanted noise.

To implement this here, Moodsonic used KScape’s Rail lighting fixture, which is embedded with loudspeakers.

“Rail was chosen over other ceiling speakers and lights not only because of the uniformity of light, but also due to the way the sound is delivered. “Unlike the vertical rain effect that ceiling speakers create, Rail surrounds the subject with a long, homogenous sound that can cover larger areas of the office space, reducing the amount of speakers required,” said Thomas Riby, Brand Manager at KScape.

Around JLL’s open, modern office, 90 Rail units are positioned strategically around work desks to provide even sound coverage at 45-60dB and provide comfortable lighting of 450lx UGR for employees either sitting or standing at their desks.

The Rail fixtures play biophilic, natural sounds generated by a Moodsonic device connected to a matrix through a K-array KA18 amplifier with 12 Rail connected to each of the 8x150W channels for audio.

For lighting, the three-channel internal DALI driver was connected to a Crestron ecosystem to control automatic daylight dimming and lighting scenes for general office environments and entertainment.

Aldar Square, Abu Dhabi, UAE

The new office space for Aldar Properties was built around connection and collaboration. Solutions from Intra Lighting help to create this community-focused environment.

Connection and collaboration are at the heart of the design of Aldar Properties’ new office space on Yas Island, Abu Dhabi.

Designed by Mustard & Linen with a specific focus on the way that people work, the space was conceived around three core principles - Connection, Collaboration and Community. These principles are translated into spaces where people can gather together, collaborate together, and where needed, isolate and use a private workroom or “pod”.

Complementing this experience, the new space incorporates a rooftop leisure area, a gym, yoga room, basketball court and outdoor terrace.

Spanning across 25,000sqm, the project is LEED platinum certified. Lighting for the offices was designed by Light Touch PLD, which specified solutions from Intra Lighting to create a scheme that would sit in harmony with the architect’s core principles.

While the interior space is dominated by a large central skylight that spreads natural lighting throughout the building’s interiors, Intra’s Trix track system, which allows for a combination of spotlights, downlights and recessed linear fittings, enabled the lighting designers to add a targeted lighting where it was needed.

With its minimalistic design, modularity, high efficiency and resistance, the Trix system is an ideal solution for flexible, fluid environments, such as modern workspaces, in which workers require a variety of spaces, each with their own lighting requirements.

From the open, communal workspaces, to the meeting rooms and individual, private working “pods”, the Trix system provides a comfortable light that helps foster a collaborative work environment, while enhancing the building’s beautiful interior design.

www.lighttouchpld.com

www.intra-lighting.com

The Event Centre, Ayia Napa, Cyprus

Illumination Physics worked with Cypriot lighting designers Archtube to illuminate the new Event Centre at the luxurious Ayia Napa Marina.

Situated on the south eastern coast of Cyprus, Ayia Napa Marina offers a unique lifestyle and experience – from luxurious residences and yachting facilities to waterfront dining options. At the heart of the 98 acre resort, built on its own jetty, lies the Event Centre.

An elliptical, organically conical glass and metal building, it is a destination venue and one-of-a-kind architectural marvel in Cyprus, designed for spacious open-air and indoor events.

Cypriot lighting designers Archtube conceived of a dynamic RGBW lighting plot that brings the Event Centre to life, creating scenes and evoking different moods and reactions, depending on the use of the Event Centre on a given occasion. To achieve this, Archtube called on fixtures from Illumination Physics.

The Event Centre is wrapped by a veil of vertical sun shade fins in five levels, each inclined progressively and slightly differently. The lighting design intention was to illuminate a pair of fins by placing a single light fixture between them at the base of each level – requiring 740 fixtures in total.

Individual control of each fixture was required to create dynamic lighting based on content; the illumination of the fins also needed to be as homogenous as possible, with light trespass to be reduced as much as the up-lighting concept would allow. A suite of different lighting programmes was therefore provided in such a way that the client could easily manually select a particular programme to suit a specific event, or as a default, an automatic schedule runs the day to day lighting displays.

Exactly how this would be done involved many calculations and evaluations, including a 1:1 mock-up in Illumination Physics’ Hong Kong office – two fins were fabricated to match the precise dimensions and profiles of the Event Centre to create a part of one of the five layers of fins.

Numerous luminaires were modelled and tested, but eventually a customised version of the smallest of Illumination Physics’ Circular Wash Light series was selected – the luminaire could be aimed in pan and tilt, which was essential since it would always need fine adjustment to be perfectly vertical in pan, and tilt was different for every fin.

The choice of LED and accompanying optics was the next challenge – 10W from a single 4-in-1 RGBW LED was sufficient in terms of power, provided it was lensed correctly. A custom lens based on an asymmetrical format was therefore developed.

Illumination Physics also designed the Artnet/DMX network and electrical wiring, and provided detailed schematics for the electrical installer to follow during installation. The system is made of a custom server for the Madrix control system running Madrix 5 lighting control software.

Great architecture deserves to be celebrated at night, but the lighting of the Ayia Napa Marina Event Centre does more than that – it conveys emotion and mood, a sense of purpose, and commands to be the centre of attention.

Central Plaza Building, Brussels, Belgium

As part of the rejuvenation of Brussels’ Central Plaza Building, fixtures from GVA Lighting help to emphasise its height and exterior appearance.

The Central Plaza Building in Brussels is a striking office building spanning a footprint of 23,000sqm. With a prominent position located near to the Central Station, it is easily accessible by public transportation as well as by car. It is also close to the central square of the city, the Grand-Place.

The building’s owner, AG Real Estate, decided to refresh the building’s architecture with a light project. Having worked with GVA Lighting on a number of previous projects, AG Real Estate engaged them to deliver the rejuvenation of the Central Plaza Building.

The GVA Lighting solutions were specified and delivered by their partner, Euroka SRL. Euroka SRL also fulfilled the role of project designer. WiiZZ Group SRL was appointed as the installation company for the project.

The brief was open for GVA Lighting to make suggestions and recommendations as to how the Central Plaza Building could be enhanced through light. GVA Lighting provided a variety of plans and designs, from which the client could choose the option they most favoured.

As part of this design stage, the client provided GVA Lighting with a budget to work to. To meet this, the number of fixtures in the chosen scheme was adjusted – delivering the desired design, while also being within budget.

The Highlighter HL-DL-NICHE-RGBW40K with Flat diffuser was selected from GVA Lighting’s extensive portfolio. The Highlighter HL-DL is a modular direct view architectural delineation LED lighting system, available in a range of monochromatic or colour changing configurations with varied mounting profile and diffuser options.

Each length of the Highlighter solution is 2,400mm, creating sleek lines that run vertically and emphasise the height of the building. The luminaires are all controlled via DMX, using a Pharos controller.

Damien Lamarche, CEO and Lighting Specialist at Euroka SRL, said: “The Central Plaza Building is a notable landmark in the centre of Brussels, particularly thanks to its prime location near to other key sites.

“The lighting scheme for the structure shows what can be achieved through light; enhancing the existing architecture and making more of what exists already, without having to commit to an overwhelming budget.

“The Central Plaza Building now looks even more iconic during hours of darkness, working in synchronicity with the glass structure to deliver a stunning result.”

House of Hungarian Music, Budapest, Hungary

Sitting in harmony with the surrounding parkland, the new House of Hungarian Music is a glimmering, ambitious new building. Fixtures from Erco help bring this new cultural forum to life.

Nestled like a futuristic, oversized mushroom in the Városliget forested park of Budapest lies the House of Hungarian Music. Designed by Japanese architect Sou Fujimoto, the House of Hungarian Music is one of the most spectacular new buildings of the “Liget Budapest Project” – an ambitious cultural forum with numerous museum buildings being built on obsolete, unused sites.

Spanning 836sqm, the music pavilion combines various exhibition and event spaces, offices, a library and two outstanding concert halls under a projecting, organically curved roof structure.

The pavilion was designed with the intention of redefining the boundaries between indoors and outdoors, between architecture and nature – through its weightless design, visitors could believe themselves to be in a clearing in the middle of the forest. Its striking canopy structure, supported by elegant pillars, is perforated by 100 crater-like cavities – through which trees grow, enhancing the connection to the surrounding park.

The transparent architecture was the determining parameter for the lighting concept; Erco downlights were installed in the glazed pavilion to avoid glare and disruptive reflections, ensuring maximum visual comfort.

In the foyer, with a ceiling decorated by 30,000 specular gold leaf-like ornaments, 350 Erco Gimbal recessed spotlights provide glare-free general lighting. The Gimbal luminaires, with focused light, imitate the incidence of natural light rays without illuminating the leaf ornaments themselves. This enables the luminaires to be precisely aligned to the gaps in the complex ceiling structure.

With a ceiling height of 12 metres, precisely directed light is essential, preventing light spill and reducing energy wastage. Erco’s luminaires function with projecting optical systems that direct the light with high precision, achieving high illuminance levels from large distances, even with a low connected load. This creates the basis for sustainable lighting, in which light is only used where it is needed.

In the basement, a permanent interactive multimedia exhibition documents the history of European and Hungarian music. Here too, high rooms characterise the architecture. The exhibition, as well as numerous screens in the exhibition areas, also had to be taken into account in the lighting concept. Erco’s Optec spotlights for track were used, as they provide precisely accentuated lighting, even at a room height of seven metres.

Outside, lighting had to comply with strict regulations against light pollution – neither trees nor sky could be directly illuminated in the park. As such, 100 Erco Tesis ground-recessed luminaires illuminate the gold leaf canopy of the glazed foyer from outside, providing poetic indirect lighting. The precisely directed light always remains below the roof construction, without causing any unnecessary light pollution.

With playful ease, the glass pavilion succeeds in creating a symbiosis between architecture, light, music and the urban woodland. Just a few minutes’ walk from the Budapest city centre, the House of Hungarian Music represents a fabulously different and sonically inspiring world.

Värnamo Hospital, Värnamo, Sweden

A new lighting scheme at Sweden’s Värnamo Hospital utilises eldoLED drivers to create a more holistic and humanistic lighting scheme, helping to put patients at ease while energising staff and helping surgeons to excel in their performance.

Värnamo, one of Sweden’s largest county hospitals, serves a population of around 96,000 people. Its architecture and design are based on a humanistic approach, aiming to provide a better hospital experience. The concept and layout aim to minimise stress and hassle related to visits and transportation, offering free hotel stays, transportation, pharmacy pick-up and church services.

The exterior has been inspired by the existing buildings and their solid brick façades with vertical and horizontal slits filled with glass and aluminum. White Arkitekter, one of Scandinavia’s leading architectural practices, worked to ensure there is ample natural light wherever people spend time. Patients can experience changing light during the day, which is hugely important for wellbeing.

Värnamo Hospital offers laparoscopy, orthopedics, urology, gynecology, plastic surgery and cholecystectomy.

Health-promotion lighting solution brand Chromaviso worked closely together with eldoLED to provide ergonomic lighting for the hospital’s operating theatres. Surgeries can be stressful and terrifying for patients and by changing the lighting, the experience can be improved.

Chromaviso’s Chroma Zona Ergonomic Lighting solution and LightBlue Controller/Control Panel coupled with eldoLED’s POWERdrive 50W offers nine custom lighting options, including red and green lighting for the monitor location, special lighting for open surgery and natural light for cleaning. Chromaviso integrated lighting control via RS232 so the staff of Värnamo Hospital can control lighting from a wall-mounted touch screen.

Implementing POWERdrive LED drivers ensured flawless dimming capabilities, flicker-safe performance, and colour consistency at low light levels. The drivers’ custom square-shaped dimming curves enhanced novel spectral compositions. To the staff, these lighting changes made a vast difference. The drivers, luminaires and controls provided much-needed contrast to the monitors for longer procedures and ensured focus during critical operations—ultimately energising staff, improving the work environment and maximising the quality of the work.

Chromaviso incorporated a warm welcome lighting powered by eldoLED’s POWERdrive 50W drivers and the Chromaviso LightBlue Controller/Control Panel. This scheme calmed the patients and ensured an orderly transition for anesthesia and surgery. Calmer patients resulted in better surgery experiences and outcomes. “The better light we have, the better we can perform”, stated Mimmi Peralta, Surgeon.

RHS Garden Wisley, Surrey, UK

One of the most visited gardens in the UK, RHS Garden Wisley now features complementary exterior lighting, thanks to fixtures from DW Windsor.

In the heart of leafy Surrey, RHS Garden Wisley is one of the UK’s most frequented gardens and one of the horticultural charity’s premier green spaces. With a splendid array of flora and fauna spread across 240 acres, Wisley is home to some of the largest plant collections in the world.

As the Royal Horticultural Society’s flagship garden, Wisley is committed to ‘Building a greener future’, and regularly embarks on improvement projects to enhance the visitor experience. The society is currently undergoing a £160million redevelopment programme encompassing several major projects, including the UK’s first dedicated horticultural scientific centre of excellence at Wisley, RHS Hilltop – The Home of Garden Science.

RHS Hilltop is surrounded by four acres of ‘living laboratories’ set in three new gardens, with the Wellbeing Garden designed by Matt Keightley of Rosebank Landscaping, and built by Mark Gregory of Landform Associates. The site is open to the public and will highlight educational opportunities and scientific work in the field of horticulture.

Lighting was a key element of the Hilltop project. It was vital that functional lighting was provided to ensure the safety of all staff and the 1.5 million annual visitors to RHS Garden Wisley.

Ben Brace, Greenspace Projects Manager at RHS, specified the lighting. Having a working knowledge of DW Windsor through previous roles, Brace approached the manufacturer to supply the exterior lighting.

DW Windsor’s Ren bollard was specified to illuminate the surrounding pathways within the Wellbeing Garden. The luminaire’s narrow profile and discreet design made it the ideal choice to aid wayfinding without interrupting the look and flow of the garden space.

Ren is offered in two widths, three heights and a range of colour temperatures from 2700 - 4000K. In addition, it utilises a unique optical system featuring reeded diffusing glass to improve lateral distribution while also delivering zero back spill. This makes Ren an incredibly versatile solution while still offering impressive lighting performance for outdoor environments, with the ability to achieve P5 lighting classes at a 6-metre spacing.

For the RHS Hilltop scheme, a colour temperature of 2700K was specified, helping to create an inviting ambience within the garden while minimising the impact on the surrounding flora and fauna.

Brace said: “Embarking on the Hilltop project has been very exciting for the RHS. While the lighting was an important part of the development, we wanted to ensure the gardens looked as stunning as possible. Ren is the perfect solution to provide function with perfect form; blending in with the surroundings and not disrupting the appeal of the green space.”

RHS Hilltop is already proving popular with visitors and is set to inspire generations of gardeners for years to come.