Illuminated River to honour Queen’s Platinum Jubilee with unique light show

(UK) - For four nights over the Platinum Jubilee Bank Holiday weekend, the Illuminated River public artwork will be lit in a celebratory sequence of evolving colour and light. The special edition of the artwork will be unveiled at sunset on Thursday 2 June and will run each night until 2.00am on Monday 6 June.

Nine central London Thames bridges, from Lambeth Bridge to London Bridge, will be choreographed in the synchronised flow of subtly moving LED light with tones of platinum and purple threaded within the main colour scheme.

Illuminated River artist Leo Villareal has been specially commissioned by the Illuminated River Foundation to programme this event, which will weave gently undulating patterns of light and colour across the historic Thames bridge structures in coordination with lighting of other major landmarks on the river.

Lord Neil Mendoza, Chair of the Illuminated River Foundation’s Board of Trustees, said: “Illuminated River is delighted to be contributing to the nation’s celebrations of Her Majesty The Queen’s Platinum Jubilee in the form of a unique lighting event along the Thames in central London. We hope that as many people as possible – Londoners, visitors and newcomers to the city alike, will enjoy Leo Villareal’s special display as part of a memorable weekend of celebrations marking the seventh decade of Her Majesty’s reign”.

Leo Villareal, artist of Illuminated River, added: “It is a privilege to create this special edition of Illuminated River to honour Her Majesty The Queen's Platinum Jubilee. The hallmark colours of the Jubilee, purple and platinum, will augment the artwork across its nine bridges over the Thames, lighting up the river and its surroundings with a momentous spectacle that people celebrating across the UK can enjoy. It's very exciting to activate so many of London’s important bridges for this unique and special moment.”

Finland welcomes new design festival to Helsinki this August

(Finland) - The inaugural edition of Design Helsinki, a brand new design festival, will take place from 24-25 August.

Finland’s capital city, which this year celebrates 10 years since it was named World Design Capital in 2012, is renowned for its functional and minimalistic Nordic architecture, and boasts the largest concentration of Art Nouveau buildings in Northern Europe, making it a key destination for architecture aficionados.

Marking a decade since it was named World Design Capital, Helsinki will celebrate the occasion wit a series of events and city-wide activities. Design Helsinki, the city’s first dedicated B2B contemporary design event, will be at the heart of the celebrations.

Design Helsinki will seek to highlight the profound influence that Nordic design, and its long-held commitment to sustainability, has on the architecture and design industries, as well as providing a platform for international design professionals to meet with sought-after, world renowned brands. The show will also work with two major partners in Finland - Habitare and the Alvare Aalto Foundation - to provide exciting and relevant content for visitors. Habitare and Design Helsinki will both feature in each other’s programmes; the creative director of Habitare, Laura Sarvilinna, will be interviewed as part of the Design Helsinki programme on “Regenerate”, while Design Helsinki will participate in Habitare’s programme as part of the theme “Blending Spaces”.

Design Helsinki will take place in various locations in and around the city, including an international pavilion in Kasarmitori, a topical Talks programme in the Design Museum, installations in Esplanadi Park, as well as within multiple resident design showrooms. The fair will also celebrate the area’s local design showrooms, who will welcome architects, designers, dealers, retailers and more to experience the best of Nordic and Scandinavian design.

SLL publishes updated Emergency Lighting Guide

(UK) - The latest edition of the SLL Lighting Guide 12: Emergency Lighting, has been published, providing up to date information on the procurement, design, installation and maintenance of emergency lighting.

The guide also provides information on how to comply with current statutory/regulatory framework and the standards regarding emergency lighting that apply within the UK.

The latest edition of the SLL Lighting Guide 12 has been developed for use when design work is to be undertaken, but also to assist engineers in evaluating existing installations against current standards and requirements of legislation.

With the previous edition published in 2015, key changes include an increased focus on the design requirements, aiming to facilitate a coordinated approach between all parties involved in emergency lighting. As emergency lighting is a life safety system, all parties who are involved carry a duty of care under various pieces of legislation to occupants of premises and are responsible for discharging their roles, whether it be as a building owner, designer, installer or maintainer.

The guide explores typical case studies, demonstrating differences in approach that may be required to address specific situations, reflecting different types and uses of premises. The document was written by a task group made up of members of the SLL and chaired by David Mooney.

Commenting on the update, Mooney said: “Good design of emergency lighting is not just a way of meeting target levels and complying with standards - it is a way of ensuring that people can orientate themselves and find their way confidently and safely through a building to a place of safety. It should be remembered that people, even in familiar buildings, may become frightened and disorientated during an emergency.”

The guidance in the document is written primarily for buildings within the United Kingdom, although there are minor variations for Northern Ireland and Scotland. However, the principles for emergency lighting are universal and can be applied to other locations if the appropriate local conditions, standards and regulations are respected.

More information about SLL Lighting Guide 12: Emergency Lighting can be found on the CIBSE website here.

Architect@Work celebrates physical return of its London edition

(UK) - Architect@Work, the curated, two-day trade fair aimed at the British architecture and design (A&D) community, returned to the Truman Brewery, London in a physical format from 13-14 April.

The 9th edition of the event saw more than 70 leading international architectural suppliers showcase their latest innovations in lighting technology, surface solutions, interior and exterior fixtures and fittings.

One of the most popular elements of the annual show was its talks programme; taking place both in person and via a live stream, this year’s series was centred upon the headline theme of ‘Air and Architecture’, which explored how we breathe and what that means for our wellbeing, as well as the lungs of cities themselves. Joining the discussion were some of the best names in the A&D industry, including: Guy Hollaway, Hollaway Studio; Joe Morris, Morris+Company; Eleanor Brough, Sarah Wigglesworth Architects; Rachel Edwards, Lendlease; Je Ahn, Studio Weave; and Julia Barfield, Marks Barfield.

Anne-Laure Van de Ginste, Exhibition Manager of Architect@Work, said: “We’re delighted to be back in London in a physical form this year. If there’s one thing that lockdowns have taught us, it is the face-to-face contact that is of the essence - especially when it comes to discovering product innovations. For us, quality clearly outweighs quantity at live events.

“In line with our long-standing commitment to championing design and innovation, our show has, once again, proved to be one of the leading destinations for the A&D community to discover new ideas and connect with their industry peers.

“We look forward to returning in London 2023 with another exciting programme of content and discussions.”

Fagerhult co-founds Healthy Indoors Alliance

(Europe) - Fagerhult, alongside Camfil, Condair and Swegon, has established the Healthy Indoors Alliance, a joint initiative to improve the healthfulness, productivity and comfort of people in commercial, public and residential buildings.

The alliance was formed out of a joint ambition to raise awareness around the vital importance of a healthy and sustainable indoor environment.

In a joint statement, the Alliance said: “Today, we spend 90% of our time indoors, at work, play and home. For this reason, it’s high time we take a serious look at our indoor environments, in order to understand their effects on our wellbeing and productivity, and to make beneficiary changes where necessary.

“While it’s true that some standards and regulations exist to guide property owners, specifiers, builders and employers, it is also true that such measures often fall short, not providing the solid basis necessary to create the healthy, productive indoor spaces we need.

“We find that despite vast scientific evidence, both businesses and consumers know very little about the tremendous impact the indoor climate has on our health and productivity.”

The initiative currently features contributors from businesses within lighting, ventilation, indoor climate control, humidification and filtration. The ambition is to address the public, developers, trades, professionals, industry, science and government institutions with the aim to educate, inform and raise awareness.

The Healthy Indoors Alliance website features comprehensive information vital to understanding how to create sustainable, healthy indoor environments. It clears up questions and misunderstandings and provides guidance for practical actions. Benefits include reduced illness, sick leave and fatigue, as well as generating greater comfort and overall wellbeing.

“The Heathy Indoors Alliance wants to drive change and make it easy for everyone to take action to improve the indoor spaces in which we spend so much of our time,” the group added.

teamLab to open permanent Borderless museum in Jeddah

(Saudi Arabia) - International art collective teamLab will open its first permanent teamLab Borderless museum in the Middle East with the launch of teamLab Borderless Jeddah.

Located in the Red Sea coastal city of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, the museum is being built on the shores of the Al-Arbaeen Lagoon, overlooking the panoramic views of UNESCO World Heritage Site, Historic Jeddah.

The immersive museum will feature more than 50 artworks, spread across its expansive and labyrinthine spaces, including Borderless World, Athletics Forest and Future Park. It will also feature an entirely new installation, created exclusively for Jeddah.

His Excellency Hamed bin Mohammed Fayez, Vice Minister of Culture, Saudi Arabia, said: “Nurturing creativity and unleashing new forms of expression is at the heart of our cultural vision for Saudi Arabia. The concept of ‘borderless’, which sees art transcend boundaries and disciplines, resonates deeply with our efforts to build global bridges, and enhance cultural understanding amongst citizens, residents and visitors. As an innovative project nestled within a UNESCO Heritage site, teamLab Borderless Jeddah promises to provide unique new perspectives, and we are delighted to collaborate with teamLab to bring this immersive, experiential concept to the Kingdom.”

Toshiyuki Inoko, founder of teamLab, added: “Jeddah is one of the leading global cities in the Middle East, with a profound history and rich cultural legacy. We are honoured to be inaugurating the site of teamLab Borderless Jeddah on the banks of Al-Arbaeen Lagoon, an exceptional location facing the UNESCO World Heritage site, Historic Jeddah.

“The concept of teamLab Borderless is that everything exists in a borderless continuity. And our work is based on the continuous accumulation of human knowledge over a long history. For that reason, it is very significant for teamLab to be able to open the permanent teamLab Borderless in Jeddah, right next to a World Cultural Heritage Site. By experiencing teamLab Borderless, we hope that people will be able to move between the seamlessly interconnected past and present, and to imagine an ideal future.”

teamLab Borderless Jeddah is a collaborative initiative between the Saudi Ministry of Culture and teamLab. The project falls under the Quality of Life programme, one of Saudi Vision 2030’s realisation programmes.

In 2020, the Ministry of Culture, Saudi Arabia entered a 10-year partnership with teamLab, as part of its mission to support and develop a thriving cultural ecosystem, in line with the Kingdom’s ongoing national transformation. The partnership aims to offer inspiration to Saudi Arabia’s burgeoning creative talents in the converging fields of art and technology.

teamLab Borderless Jeddah is currently under construction, with an official opening date to be confirmed soon.

Tryka LumiNode

Tryka’s new LumiNode product helps create a truly stunning LED façade, illuminating any project into an instantly eye-catching vision. This innovative fixture offers an ultra-lightweight design and compact dimensions that ensure a discreet installation. Not only does it offer a sleek and subtle integration, it can also be made-to-measure to suit the specific needs of any project. This flexible solution offers the perfect lighting for architectural, entertainment, or general lighting application areas.

LightGraphix LD34MI

Since introducing its high-power inground linear wall grazer the LD34, LightGraphix has received many requests to design a mains-in based system. The company can now share the LD34MI with an IP67-rated plug and play system for speed and ease of installation on-site. It can support single length, multiple length and inline, switched and dimmable applications and removes the need for remote driver locations. LD34MI’s high-power performance matches the LD34, delivering up to 3749lm.

Erco Beamer New

The lighting technology of Erco’s highest-output museum spotlights is now also conquering outdoor applications in the form of the Beamer New range of projectors. The first of their kind to feature darklight lenses, the luminaires offer unrivalled variations in terms of digital control modes, interchangeable lens units and mounting options. They are predestined for sophisticated outdoor lighting tasks with their quality of light and outstanding visual comfort.

Emco Here & After

This comprehensive linear lighting system gives you maximum flexibility as well as significant cost savings from rapid, easy installation – even for complex layouts and control specifications. Different Hybrid modules for your preferred combinations of general lighting, downlighting, spotlighting and wall washers. It can be used with multiple electrical circuits and complex lighting networks and control systems; you can also choose from a wide range of matching aluminium covers, rails and accessories.

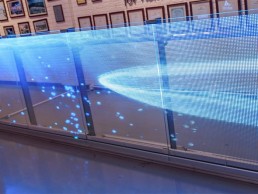

FlexLedLight LED-in-Glass

The LED-in-Glass screen is bright enough to be installed as a window facing the sun while offering 92% see-through both ways. Its sizes range from three-metres high for shop windows to 1.5-metres high guard-rail or 0.5-metres high smoke containment screens while there is no limit to the lengths. Pitches are 10mm or 8mm to push advertising messages, light effects or videos of any type.

Spectrum Lighting CR2

CR2, the ultimate cylindrical lighting instrument: small and powerful, visually striking yet unobtrusive and small enough to disappear into the architectural background. When fitted with decorative bezels and/or Spectrum’s luminous frosted accent acrylics the CR2 is also capable of being an architectural feature. Set the mood with warm dim LEDs or choose from five kelvin temperatures at 80 CRI or from four kelvin temperatures at 90 CRI.