Sally Storey publishes new book

(UK) - Sally Storey, Founding Director of Lighting Design International and Creative Director of John Cullen Lighting, has published a new book in partnership with RIBA Books.

Entitled Inspired by Light: A design guide to transforming the home, the book aims to provide practical insight to designers with an abundance of visual inspiration on successful lighting solutions and schemes - from the fundamental principles of lighting design, to working with LEDs, to advice on lighting unusual spaces.

Accompanied by lavish photography and accompanying lighting plans, Inspired by Light looks to showcase the most up-to-date information on trending and lighting technologies that aim to transform how light is used within a space.

Speaking of the new book, Storey said: “With the arrival of LEDs, which revolutionised the industry, I felt that a book that explored how to use this new tool would be of benefit to the industry. There is very little advice currently available for designers and the design savvy to fully understand how to select LEDs. The outlining of all the important technical elements within the book is critical to the understanding and proper selection of LEDs, and to illustrate the various techniques that can be used and how they are important to distinct styles of interior.

“Good LED technology has allowed for greater opportunities and benefits within the industry, due to its miniaturisation, which allows for more discreet integration into architecture and joinery. With LEDs lasting longer than ever before, it is so important to get the lighting right from the outset or it will be a costly mistake.”

Throughout the book, Storey draws inspiration from across the UK and around the globe, including a contemporary villa in Dubai and an alpine chalet, and presents a variety of interior and exterior real-world projects old and new large and small.

With its visually engaging and approachable style, it is hoped that the book will provide a fascinating insight into current and emerging lighting technologies, and will appeal not only to architects and designers, but anyone interested in making the most of lighting at home or at work.

Inspired by Light is available now on the Riba Books website.

www.lightingdesigninternational.com

www.johncullenlighting.com

SLL to publish new guidance on protecting nighttime environment

(UK) - The Society of Light and Lighting (SLL) has published its first Lighting Guide dedicated to protecting the nighttime environment.

Lighting Guide (LG) 21: Protecting the Nighttime Environment aims to set out the consequences of light pollution and the right questions to ask when designing exterior lighting schemes. It considers common applications, including façade lighting, heritage buildings, sports lighting and security lighting. It also outlines potential mitigation measures.

The late Liz Peck, Past President and Fellow of the SLL, carried out most of the work on LG21 in the months before her death in January 2021, bringing it very near to completion.The guide was then completed and prepared for publication by Benedict Cadbury of Lampholder Lighting Design.

Whilst working to develop further practical guidance on the application of lighting design for the protection of the night-time environment, the Society felt it prescient to recognise Liz’s commitment and dedication in producing this Guide.

Within the forward, SLL immediate past president, Bob Bohannon MSc, FSLL, MIET wrote of his friend and colleague; “I had the privilege to work alongside Liz on the Iron Bridge at Telford project and on reading this guide it was good to see just how much of the knowledge and advice set out within it were incorporated into the lighting design of the Bridge. Liz had long expertise in mitigating the negative effects of lighting on bats and I had long experience in delivering zero direct

upward light schemes, so this guide could almost have formed a checklist for the project: skyglow, obtrusive light, bat flyways, fish, visitor views, extending the economic day of Ironbridge, curfews, luminance-based design, spectral reflectance and light source spectral radiation, daytime appearance, glare mitigation through positioning, aiming and louvres and finally an overall lighting impact assessment — all were included.”

The appendix includes a list of protected species as identified by the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, which include the 113 vertebrates, together with 68 invertebrates (butterflies, moths, insects, and marine species) and 176 plants. (There are some further species of which the sale/offer for sale is prohibited). Badgers are treated separately under the Protection of Badgers Act (1992).

Members of the Society of Light and Lighting receive unlimited online access to all Guidance from the SLL and the Chartered Institute of Building Services Engineers, with the option to purchase hard copies at a reduced rate. All guidance is available to purchase as pdf or hard copy on the SLL website.

Wila confirmed as Carbon Neutral organisation

(UK) - Wila Lighting has confirmed its green credentials, securing its position as a Carbon Neutral company.

The standard is awarded by Carbon Footprint Ltd; an organisation working with blue-chip and mid-market companies to support them in reducing their carbon emissions and engaging in carbon offsetting.

As part of its work, Carbon Footprint Ltd awards an industry-recognised standard to those companies that can demonstrate their carbon footprint status. To achieve this, organisations must complete a carbon footprint appraisal.

For 2021, Wila has gone one step further and has been recognised at the highest level of Carbon Neutral+ standard. This demonstrates their commitment to supporting a range of additional environmental projects.

Since 2008, when Wila committed to a carbon offsetting programme, the organisation has reduced its carbon emissions by 84%. This demonstrates the company’s true dedication to not only offsetting to neutralise, but also actively reducing their initial output, which they have achieved significantly over the past 13 years.

As part of their carbon neutral activity, Wila has chosen to support a UK tree planting project. In addition to VCS offset – a project that aims to reduce deforestation in Brazil – trees will be planted that will sequester carbon over their lifetime, as well as providing habitats for wildlife.

Matt Vogel, Managing Director from Wila said: “We’re very proud of our work over the past decade to offset our carbon emissions, as well as significantly reducing our initial output. Our team has worked hard to achieve the Carbon Neutral+ Standard, and we continue to be committed to being more sustainable in our activities and processes.”

Recolight gives update on sustainability initiatives

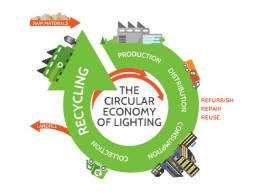

(UK) - At a press briefing this week, Recolight CEO Nigel Harvey gave an update the company’s sustainability initiatives.

“Over the last two years, we have run nine webinars regarding resource efficiency and the circular economy,” he said. “We are delighted those webinars were attended by 1,200 delegates, and were also viewed by 1,500 afterwards. It is particularly pleasing that the topics are now moving on from ‘what we should be doing’ to ‘what is being done’. Particular thanks to Ray Molony who has chaired all the sessions, and has been instrumental in encouraging the lighting industry to embrace the circular economy.”

Harvey added: “Next week Recolight will be launching two new services intended to increase re-use and re-manufacture in the lighting industry, by diverting more product from recycling. The services will address the re-use of used lighting equipment, and also the supply of end-of-line or remaindered stock held in our producer members’ warehouses. These services have been developed directly as a response to the challenges explored during our webinar series.”

Harvey then moved on to give an update on Recolight’s net zero ambitions: “We are committed to being net zero by 2030. Data for our benchmark year, 2019, has been independently analysed. It shows that more than 90% of our carbon emissions arise from the transport of waste around the country. We have to get that down. It will be a challenge, because our waste is currently transported by diesel fuelled HGVs, but we are determined to find solutions.”

Harvey concluded by saying: “I am immensely proud of team at Recolight. They are making a major contribution to the sustainability in the lighting sector by supporting our Producer Members and their customers in their ambitions to adopt circular economy practices.”

[d]arc room pop-up @ Design London a success

(UK) – [d]arc room returned to London for special pop-up event

Returning to London for its fifth year, [d]arc room hosted a special pop-up event at Design London (previously 100% Design), which received a staggering 12 and a half thousand attendees.

Recognising the capital’s profound influence over Architecture and Design specification, [d]arc room pop-up was a new and enhanced event experience underpinned by the wealth of knowledge of both [d]arc media and Media 10, organisers of Design London.

In previous editions of 100% Design, the lighting contingent was sporadically positioned throughout the exhibition. This year saw [d]arc room pop-up as an established lighting area within Design London.

The pop-up featured a highly curated selection of lighting brands providing a unique platform for suppliers and designers to meet at what was the must-attend event during London Design Festival.

Confirmed exhibitors included Seoul Semiconductor, Franklite, Delta Light, ILP, iGuzzini, John Cullen Lighting, Thorlux Lighting, Mesh, Tryka, IALD, Nichia/Formula Luci, Light LAB, RAY Lighting and SLL.

The pop-up event also showcased this year’s [d]arc awards light art installations based on the theme ‘The Spectrum’. Displayed on the Magazine Mezzanine for the duration of Design London, a [d]arc night party celebrating all this year’s awards winners was also be held on the Wednesday evening.

This year’s installation teams included: Arup / Lumascape; Buro Happold / TLS; Hoare Lea / Seoul; Lighting Design International / LedFlex; Nulty / Erco; and Studio-29 / Kingfisher Lighting.

A series of lighting talks, [d]arc thoughts, also took place on the Magazine Mezzanine. The panel discussions were a huge success, drawing large audiences each day to listen to an esteemed line-up of industry professionals discussing topics around lighting, plus a special series of Diversity in Lighting.

www.darcroom.com / www.designlondon.co.uk

Lutron releases Athena architectural lighting solution

(UK) – Lutron brings Athena architectural lighting solution – with iOS App Control – to the global market.

Athena is inspired light that delivers a holistic experience – a simple, flexible, all-in-one solution for lighting, intelligent blinds, and connected apps.

Lutron Electronics brings the Athena architectural solution to global applications. Athena is a simple, flexible, all-in-one solution that elevates everyday experiences with the magic of light. The system marries world-class control, flexibility, and simple app-based setup in a lighting control solution that is optimal for both new construction and retrofits and is ideally suited to handle the evolving needs of commercial spaces. Especially now, as commercial spaces are rethinking occupancy patterns and ease of use, Athena is built to meet today’s uncharted design challenges while delivering flexibility for the future.

Key features include:

- Universal fixture control – control all load types from a single product with no minimum load requirements.

- A right-sized processor accommodates design and budget in both small and large spaces with no limit to the number of DALI zones making it ideal for intimate restaurants, art galleries and museums, and hotel public areas. Athena is designed for seamless integration of lights and blinds to deliver a beautiful lighting environment.

- Simple-to-use, the mobile iOS application for real-time programming and personalisation includes features such as fade times adjustable to up to four hours.

- Seamless API integration to building management systems for centralised monitoring and control. Athena is designed to deliver quality light, natural light, a connection to the outdoors, and control options that are focused on enhancing the human experience.

“Across the globe, building design and customer expectations are changing to reflect a more human centric lighting experience. As designers and business owners navigate new challenges, Athena offers a solution that supports the human experience and celebrates nuances in design and culture. For today’s lighting designs, flexibility and simplicity are paramount. Athena is built with this in mind,” said Olivier Perrigueur, Vice President and General Manager, Commercial Business at Lutron.

Most people spend their days under static light that doesn’t change. Athena invites architects and designers to change this paradigm, to extend dynamic natural light deep into the built environment, far beyond the window’s reach. Athena brings the full power of tuneable white, DALI Type 8 fixtures to the designer’s fingertips. With best-in-class fade times, and independent control of colour temperature and intensity – from 100% to 0.1% – create perfect harmony between interior light and natural daylight.

Athena expands opportunities for beautiful light in elegant spaces. Customise lighting designs with warm dimming and tuneable white control. The simple, mobile app enables dimming to 0.1% light with precision fine-tuning in 1% light level increments for visual presentation and aesthetics that are unique in each space. Customised controls are also available to meet the needs of occupants and visitors alike – touchless, responsive options like occupancy and daylight sensors or timeclock control, individual Pico remote controls and luxury aesthetics such as Palladiom keypads, or the all-new Athena Touchscreen, and mobile app integration ensure the right options for each space.

Athena processors allow the system to scale easily, making Athena systems as good for small architectural spaces such as restaurants, museums, and boutiques, as they are for large, open-plan office spaces and corporate headquarters.

New CEO for ILP appointed

(UK) – The Institution of Lighting Professionals (ILP) has announced the appointment of Justin Blades as its new Chief Executive Officer, succeeding Tracey White, who is relocating abroad.

Blades will assume the role on 1 November, and has a strong mandate to further enhance the organisation’s role in uniting the skills of engineering, design and technology in order to deliver quality lighting for the built environment.

Fiona Horgan, ILP President, said: “The Board welcomes Justin to the ILP team as our new CEO. We are excited to work with Justin at this critical time for the lighting industry as we look to address the social and economic challenges of the Covid-19 pandemic and climate change.

“As we look to the future, Justin has already brought to the table some great ideas and brings experience from a membership body organisation.

“The Board would like to thank Tracey for her leadership and work raising the ILP profile over the past three and a half years, she has provided us a voice at national level and will be missed by all who have worked with her. We wish her all the best for her new life in the sunshine.”

Speaking of his appointment as CEO, Justin Blades said: “I am delighted to be joining the ILP as CEO and I look forward to working with ILP members, the Board and the wider team to focus on extending the reach and voice of the Institution for new generations of lighting professionals, building on the significant work that has already been accomplished.”

Prior to joining the ILP, Blades held senior positions in the membership sector, including six years as Deputy Chief Executive of the Institution of Chemical Engineers, one of the largest chartered professional engineering institutions in the UK.

IES & IESSA announce Joint Memorandum of Understanding

(USA) – The Illuminating Engineering Society (IES) and the Illumination Engineering Society of South Africa (IESSA) have announced a memorandum of understanding (MOU), enabling future collaboration on consensus-based guidelines and publications.

Both parties seek to advance lighting knowledge and to provide a forum for business, training, public engagement, national standards and meaningful engagement within the lighting industry both nationally and internationally.

“With the fast pace of technology transformation in the lighting industry, it is becoming more and more challenging to keep every stakeholder educated and updated in the field of lighting,” said IESSA President Daniel Kasper. “Through our global collaboration with the IES, we aim to positively impact society and the environment while strengthening each other along the way.”

The IES and IESSA have agreed to establish a mutually beneficial relationship between the parties that will encourage coordination among each organisation’s documents, where appropriate and, when mutually beneficial, create joint documents, share in educational opportunities, designate committee representatives and advocate for each other’s organisation. Potential research projects and increased participation in committee activities are anticipated.

IES Director of Education Brienne Musselman added: “Formalising relationships with organisations such as the IESSA will support our efforts to educate, advocate and engage with the global lighting community.”

Recolight announce autumn webinar series

(Online) – Recolight has announced that its webinar series on the Circular Economy of Lighting will continue into the autumn, with three news sessions to be chaired by Ray Maloney.

“There’s definitely a shift in attitudes happening in the lighting industry, and we’re starting to look seriously at the implications of adopting circular economy principles. Companies that ignore this shift risk looking out of touch,” Maloney said.

The sessions, held on 16 September, 7 October and 28 October, will cover ‘The specifier’s role in the Circular Economy’, ‘Extending the life of luminaires’ and ‘Designing sustainable luminaires’.

During these webinars, a range of lighting producers, specifiers and designers will share their insight and positive initiatives being undertaken to reduce the impact on the environment. Defra will also provide input on how they may encourage and incentivise product reuse.

Recolight CEO Nigel Harvey added: “The Recolight webinars have brought together the lighting industry, helping all to adopt a Circular Economy approach. Much progress has been made since we started, not just with action undertaken by the industry, but also legislation.

“The generosity of our panelists to share their knowledge and experience is invaluable with helping to move the industry towards a sustainable model. It has been genuinely heartening to see the continuing high level of interest and attendance our webinars have attracted.”

All sessions are free to join. More info on how to register can be found on the Events tab of the Recolight website.

Trilux announce partnership with Smart Building Technology specialist

(Germany) – In an effort to simplify the integration of lighting into the hardware and software infrastructure of digitised buildings, Trilux has invested in IT expert wtec.

wtec specialises in building automation and IT infrastructure, its smartengine technology enables the complete lighting network to be implemented via data cabling and seamlessly integrates into the building management system.

With an investment of 25.1% in wtec, a subsidiary of German real estate developer Zech, Trilux aims to expand its competence in IT and building automation, strengthening its position as a holistic room and building solutions provider.

Particularly in the development of newly planned office buildings, digitalisation and automation of services will soon play a central role – by integrated IoT system modules, lighting will increasingly take on tasks in the future that go beyond the classic lighting tasks.

“The lighting network acts as a flexible technology carrier that is responsible for communication and control of the other trades, becoming the backbone of digitalisation,” said Joachim Geiger, CSO at Trilux. “Futureproof lighting provides high-quality and efficient light, and at the same time makes the room and building smart.”

Dr Frank Schmitt, Managing Director at wtec and General Manager Smart Buildings at the Zech Group, added: “The IP conversion of secure internet use of building data is the logical and necessary step towards more customer benefits. We are pleased that with Trilux we have a strong partner at our side for our growth and our path to a technological standard.”

SLL Ready Steady Light to return this Autumn

(UK) – One of the Society of Light and Lighting’s (SLL) flagship events, Ready Steady Light will be returning this Autumn. Taking place in partnership with Rose Bruford College, the competition will take place at the college’s leafy Sidcup campus on 19 October.

As is tradition, the SLL is inviting teams of lighting professionals to compete against each other in a back-to-basics celebration of the art of science and light. Each time will be challenged with creating an exterior light installation, with a limited range of kit in just 180 minutes.

“Whilst the lighting community has worked to overcome the challenges presented by the pandemic, day to day work has continued. There have been new starters and the same requirements to support development but without the crucial interaction that comes with working alongside colleagues in a shared space,” the SLL said. “The Society feels it is more important than ever to provide design practices and lighting professionals with an opportunity to have fun and work together, with the added element of some friendly competition.”

As in previous years, there will be three awards up for grabs. A panel of expert judges from the SLL and the IALD will decide the winners of the Technical and Artistic Awards, with the Peer Prize decided by the contestants taking part.

Students enrolled in Rose Bruford College’s Lighting and Design BA courses will support the event, with the opportunity to learn from and assist lighting professionals working in this unique environment.

Previous winners have included dpa lighting consultants, UCL, WSP, Arup, Hoare Lea, Speirs Major and AECOM.

More info on how to register your team for the event can be found online here.

LED Expo brings focus on women in lighting industry through virtual LED Summit

(India) – Supported by the IALD and event partner K-Lite Industries, Messe Frankfurt India held an online webinar, LED Summit, which sought to unite successful women entrepreneurs from the lighting industry to address the challenges that female employees continue to face in the arena of lighting.

With the IALD as the knowledge partner, the LED Summit webinar organised earlier this month, united some of the most influential and successful women entrepreneurs from the lighting industry to discuss the topic of ‘Women & The Lighting Profession – Understanding their role’.

The panellists were forthcoming in highlighting the struggles and prejudices they face as women in the lighting profession: “In academics, there are a vast number of women going in to learn lighting design, but very few of them actually end up becoming a part of the industry,” shared Shailee Trivedi, IALD Member and IIID (Institute of Indian Interior Designers) Chair Elect.

Further elaborating on the issue, Surbhi Jindal, who is also the India Ambassador for Women in Lighting (WIL), added how WIL has been working relentlessly to profile, celebrate and support the women working in lighting. She also shared how women are facing the brunt of the severely affected job market due to the current pandemic.

The event partner for LED Summit, K-LITE actively seeks to create opportunities and support aspiring women. The company employs more than 50% women under its workforce across the spectrum.

An influential lighting professional herself and one of the panellists at the virtual session, Sharmila Kumbhat, Director, K-LITE described the significance of women employees and leaders in the industry: “Lighting being both an art and science, women by their very nature have the insights and temperament for art, architecture and design. Yet it is important to overcome these gender barriers and allow talent to come through regardless of gender.”

Empowerment of women in lighting profession is not only a case of gender equity but more so about celebrating the accomplishments of female professionals to inspire the next generation of women workers and decision makers.

As one of India’s leading lighting trade fairs, LED Expo aims to continue to provide a B2B platform where lighting professionals can gain equal access to sourcing and networking opportunities through its New Delhi edition, scheduled to take place on 18 – 20 November 2021 at India Expo Mart, Greater Noida.