Women in Lighting Global Gathering Survey now live

(Online) – During Covid, Women in Lighting (WIL) created a one-day virtual event for International Women’s Day, the Global Gathering. Throughout the day, the event shifted focus from Asia Pacific, to Europe, to Middle East, Africa, and the Americas, running alongside a social networking feature where attendees could connect with other members around the world. The popularity of the event meant that it was repeated in 2022.

In 2023, instead of connecting the community together in this way, the project decided to undertake a “Global Gathering” of data instead, launching a survey that hoped to examine the lighting profession in the context of the theme of International Women’s Day 2023 – Embracing Equity. The aim was to gather a comprehensive impression of the lighting industry both in terms of where it was thriving, and where it needed to improve in the area of gender equity. The hope was that the results would provide a valuable contribution to the profession as a whole, or at least create a “line in the sand” for future evaluation and thought.

WIL called upon its community and supporters to assist in creating a global gathering of information by completing a survey, aiming to investigate and ultimately embrace equity in regard to working practice in all aspects of the lighting industry – the survey was open to and welcomed input and information from all genders.

A year on from the survey opening, WIL has published the findings in a Global Gathering report, available to view on the WIL website.

Almost 800 people completed the survey from across 73 countries, with the majority of participants being women (69.1%). Analysing the findings, WIL said: “We learnt that we are not questionnaire experts, and despite the majority of participants making no comment on the survey’s content, a section of people felt the questions weren’t relevant to them, in particular people who were self-employed or in entertainment felt that the survey wasn’t applicable in all instances. We appreciate all the comments as it allows us to improve should we undertake something like this again.

“We are not data experts either, so the pages that follow are not analysed or accompanied by judgement. They just present the data as given and are therefore available for those interested to interpret as useful.

“There are some extremely interesting data slices – some are very positive. For example, it’s great to hear all of the positive policies that many companies have in place. Some are very negative – the high percentage of people reporting on sexism and racism in the workplace is alarming.

“We have tried to intersect some of the data that we found particularly interesting. If there is something that you would like to know that we have missed, or is of special interest to you, please contact us and we will happily share that particular slice of information.

“We welcome everyone to join and to be part of inspiring women everywhere and helping us to grow the network wider, ultimately supporting diversity and equity in all aspects of lighting. We want everyone to join in because we only get better together.”

The full report can be found on the WIL website here.

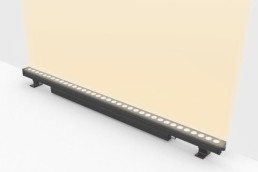

LEDFlex - Rigid Optico

Introducing the Rigid Optico: a robust, dynamic optical fixture engineered for exterior wall washing. This versatile solution boasts an array of colour options, from single white to dynamic white, RGB/RGBW, and pixel configurations, alongside adjustable colour temperatures and beam angles (single: 8° to 60°; dual: 10x40° to 20x50°). Designed with overheat protection, IP67 rating, and a resilient operating temperature of up to 55°C, it thrives in harsh outdoor environments. With an impressive efficacy of 100 lm/W and an optional marine-grade variant, experience unparalleled performance. Visit LEDFlex at Light + Building Hall 3.0 Stand F51 to witness the grand reveal.

Luminii acquires Glint Lighting

(USA) – Luminii has announced the acquisition of California-based Glint Lighting. The move expands Luminii’s North America presence, bringing new product innovations to its growing roster of architectural lighting solutions, while enabling the company to further innovate new LED lighting technologies and products that service commercial and residential markets.

Jeff Parker, CEO of Luminii, said of the acquisition: “We welcome Glint into the Luminii family. As we embark on this exciting journey with Glint, we’re not just acquiring a company; we’re fortifying our company vision.

“At Luminii, our commitment lies in introducing highly discreet solutions that seamlessly blend form and function. The addition of Glint enhances this commitment, bringing together their expertise in wellbeing-focused products with our legacy of innovation in architectural lighting. This collaboration propels us to engineer fresh possibilities, both within our current product portfolio and in exciting new solutions on the horizon.”

By integrating the Glint collection of highly adjustable luminaires, Luminii is poised to unlock a myriad of innovative opportunities for its diverse customer base. With a strong presence in key market segments including museums, galleries, retail, hotels, restaurants, residential, and casinos, these lighting solutions are ideal for environments seeking an effortlessly adaptable lighting approach.

“We are thrilled and see no better collaborator to expedite the success of the Hero product line,” added Peter Kozodoy, CEO of Glint Lighting. “Luminii’s vision and complementary product strategy seamlessly aligns with ours, making this decision a straightforward one for our team. Fuelled by our award-winning innovation and dedicated focus on optical systems R&D, combined with Luminii’s proficiency in linear expertise, we recognise an extraordinary opportunity to propel our products even further in the lighting industry.”

www.luminii.com

www.glintlighting.com

MYS Hotel, Thailand

Nestled in the mountains of Khao Yai, the MYS Hotel is a luxury, boutique destination that fuses Scandinavian and Thai design. SEAM Design developed a lighting scheme that seamlessly blurs the interiors and exteriors of the space.

Fusing contemporary Scandinavian and Thai-inspired design, the MYS Hotel is the newest boutique destination in Khao Yai, Thailand.

Blurring interior and exterior spaces, the luxury resort provides a calming retreat amidst verdant greenery, giving guests a beautiful spot in which to relax and unwind.

Lighting for the stunning new hotel was designed by SEAM Design, and one of the main parameters of the scheme was to delicately merge the modern and natural elements together into one cohesive ambience.

Aticha Padungruengkit, Associate at SEAM Design, explains: “The project serves as the ideal retreat for those seeking proximity to nature while preserving their privacy and enjoying high-end services. Achieving this balance involves a thoughtful lighting design that facilitates wayfinding without being overly conspicuous, ensuring a harmonious blend of natural surroundings and modern amenities.

“The overall concept for the lighting was to establish a sense of comfort that harmonises with nature, while infusing a subtle element of surprise. The lighting scheme is crafted to complement the distinctive architectural design – we hope that guests will always remember the unique character of the MYS Hotel and want to come back.”

To realise this harmonious concept, the lighting design team conducted “extensive studies and research” to ensure that the lighting struck the required, delicate balance that would be “sufficient to create an inviting mood and atmosphere for guests without disturbing the wildlife and natural surroundings,” Padungruengkit adds.

Lighting control is used to ensure the appropriate amount of light is provided at the right times. During late-night hours, only wayfinding lights are activated, with lobby lighting dimmed while not in use, allowing for only a special light setting to remain on.

One of the defining features of the hotel is its remarkable “levitating” outdoor pool; reaching out over the hotel lobby, the pool is connected to a lounge café that opens to expansive, highly curated gardens across the hotel grounds.

Padungruengkit explains how the lighting helped to further showcase this standout feature: “The distinctive feature of the project is the levitating pool, easily visible from the main road in its elevated structure. We wanted to emphasise this ideal by incorporating vibrant colours into the pool, making it particularly prominent during nighttime from a distance. As guests pass through the gate to the drop-off area, they are welcomed by the watery floor that mimics the visual effect of the pool above, creating an immersive underwater experience.”

The use of dynamic colours and movable lighting helps to further distinguish the reception area and set it apart from the rest of the hotel, but Padungruengkit explains how the lighting design shifts throughout the space to create pockets of distinction and enhance the overall guest experience. She says: “As guests move to the wine bar and restaurant, the ambient lighting and textures gradually lower to create a formal and refined ambience suitable for fine dining.

“In the guest rooms, lighting is customisable, allowing guests to tailor the brightness to their preferences. A brighter setting is available for work or other business activities, an evening scene promotes relaxation, and a night scene is designed to facilitate a peaceful night’s sleep.”

Padungruengkit adds that the illumination levels across the various areas of the hotel were designed to blend from space to space with minimal variation, while low-level lights, while providing different effects and functions, are similarly placed in terms of height and rhythm. These strategies, she explains, were used to seamlessly connect one area to another.

That being said, the nature of the resort, and its merging of interior and exterior spaces, did provide a degree of difficulty for the lighting designers, as Marci Song, Director at SEAM Design, explains: “Blending across a fully glazed threshold between interior and exterior is definitely one of the biggest design challenges, particularly on a project in a mountain-side setting where there are hardly any buildings in sight.

“When it comes to fully glazed partitions, the challenges are twofold: firstly, ensuring that the light spill from interior to exterior does not negatively impact the magical expression of the surrounding landscape and landscape lighting; and secondly that fully glazed openings allow views outward towards the beautiful vistas of the mountains, but they also allow for views within the rooms and villas. Careful positioning of lighting, optical accessories, and controlled scene settings all help to tune the light on both sides of the glass to increase privacy for the guest when and where needed.”

Given the hotel’s beautiful surrounds, Padungruengkit adds that the lighting was designed with the idea of “facilitating a close connection with nature”, something that was posed to SEAM Design by the project architects, Urban Praxis. “We seized this opportunity to enhance the lighting scheme by developing creative concepts, delineating areas to be subtly and elegantly highlighted, while other areas were intentionally subdued to preserve the natural environment and privacy,” she says.

This is but one example of how the design team worked in harmony across the board to achieve the desired, high-end finish, as Padungruengkit continues: “We worked closely together with the design and consultant teams from the project’s primary concept to ensure a unified vision among all team members.

“During the detailed development stage, effective communication and coordination with the team became even more crucial, as the intricacies of lighting had to integrate with both architectural and interior details perfectly.”

Being in close contact with the wider design team from an early stage also served to avoid any would-be structural issues later down the line, once the project got underway, as Song elaborates: “Structural constraints for lighting would need to be mitigated in the early stages of the design. We were lucky to be brought on board during stages two and three, where we had a chance to coordinate key details with structural engineers.

“Sometimes, when we are brought in too late, the structures are fully coordinated, and we are only left with attaching rather than integrating the light. Other design opportunities could have been missed if we were not brought in for the early adoption of lighting.

“The design is quite modernist, meaning that the buildings and structures are clean, and in a way monolithic, with very few embellishments. So, rather than attaching fittings for an expressed lighting approach, which is common in luxury and hospitality projects, we had to come up with clever and creative detailing. The luxury refinement is in the shaping of light with finessed details, rather than deploying luminaires with refined finishes.”

With the majority of the common spaces of the hotel open to the elements, the SEAM Design team had to work to find luminaires that would be durable and robust enough to withstand external use, yet available in the quality finishes and small sizes needed for a luxury environment. A tough balancing act to achieve, but Song explains that the team was able to find the necessary products needed to create the required ambience from local suppliers, where possible. “We do our best to find locally sourced products,” she says. “We worked closely with local suppliers and manufacturers to find high-quality luminaires that rival the European market. Where we can, we try to cut down on carbon footprint related to transportation, replacement materials and lighting equipment is supplied by the local and regional market with shorter lead-times for better support and customer service to the operator.”

Completed in 2023, the MYS Hotel provides guests with a magical mountain retreat, with the fusion of Scandinavian and Thai design providing a contemporary, yet calm destination where they can immerse themselves in the beautiful Khao Yai surroundings.

The lighting from SEAM Design only adds to the experiential nature of the resort, with Padungruengkit satisfied with how it fits within the overall visitor experience. She says: “Lighting can prioritise different areas of the resort, ranging from the entrance spaces where anyone can appreciate the captivating design of the lobby or indulge in a fine dining experience, to more private areas within the hotel building reserved for guests. The subdued illumination within the hotel rooms and pool villa, coupled with strategically positioned light sources, contributes to a sense of privacy.”

Looking back on the project, Song is also satisfied that the collaboration on show has bore fruit, leading to a “magical” destination for guests. She concludes: “The project team, including the design team and the client team, were highly collaborative from beginning to end. While there are numerous resorts and vacation spots in the area, it felt like we were all working together for a common goal of creating a truly special place for Khao Yai. We think that we have achieved that.”

Oman Across Ages Museum, Oman

One of the strongest statement pieces of architecture in the Middle East, the Oman Across Ages Museum launched earlier this year - designed by Cox Architecture, with lighting design by Lighting Design Partnership International.

Situated in Manah, near Nizwa, the crossroads of Oman, the Oman Across Ages Museum is a cultural and educational hallmark both for Omanis and visitors to the country.

Commissioned by the Royal Court Affairs, Sultanate of Oman and designed by Australian firm Cox Architecture, the legacy project of the late Sultan Qaboos bin Said has delivered one of the strongest statement pieces of architecture in the Middle East.

Inspired by the extraordinary landscape and geometric profiles of the Al Hajar Mountains and its canyons, the museum was designed to showcase the unique characteristics and historical significance of the Sultanate of Oman, and comprises a knowledge centre, an auditorium, permanent and temporary exhibition galleries, a vast garden, and several dining venues.

The museum’s design uses the full array of architecture’s potential for expression and communication, including scale, geometry, form, light, and vistas both as purely expressive devices, and to offer a wide range of possibilities for installations, displays, and performances across its varied spaces.

As a cultural landmark, the museum transports visitors across the nation’s 800-million-year history through a series of immersive, high-tech experiences. The building emerges from the landscape as a series of angular, geometric forms that sit in dialogue with the backdrop of the peaks and ridges of the Al Hajar Mountain range. In harmony with the architecture, the exhibition design celebrates Oman’s rich heritage, dating from prehistory to modern day through the latest immersive technologies.

Lighting Design Partnership International (LDPi) was appointed at the outset by Cox Architecture, curating and crafting a lighting story and journey that is embedded in the grain of the architectural philosophy. The teams from Cox and LDPi worked alongside each other in a united narrative to deliver a holistic solution to an outstanding piece of architecture and form.

Lawrie Nisbet, Managing Director at LDPi, tells arc how the museum’s unique architecture guided the design: “The architecture design has such a strong narrative that as “architects with light”, our duty was to enhance that narrative and develop our own lighting story. The story that we developed was a journey based upon visitor experience, both from approach and through the building and its form.

“The journey commences at the outset as that of a typical visitor; departing from Muscat and travelling through the Al Hajar mountains to the plain of Manah, where the site is located. On appointment, the first thing that LDPi did was to physically travel that journey. The whole approach and the illuminated experience were developed from that original journey experience.”

Nisbet explains further how, once this concept was developed, the design team brought it to life: “By immersing ourselves with the architecture and form; integrating nearly every lighting solution within its physicality; by defining the lit condition through limited fully integrated solutions; by minimising visual disturbance, visibility of source and crafting the effect of light and form sinuously.

“Much work was done by hand drawing and sketch. Renders were simple Photoshops and have proved to be the exact embodiment of the reality. This project was all about the true understanding of form and material and the interaction of light in all its forms. The results are beyond calculative and prove the point that only the ‘design eye’ can create such synergy with built form and materiality.”

The idea of taking visitors on a journey continues inside the museum – from the outset, the experience is one of stepping into a place of holistic drama and sensory stimulus. Visitors journey through a series of unfolding spatial sequences that progress from the raw naturalistic beauty of the soil and rocks to spaces of increasing volume, refinement, and lightness.

Throughout this journey, LDPi worked in close harmony with the architects, designing a lighting scheme that sat in sync with the building’s form, highlighting its scale and architecture. Nisbet adds: “Our design alignment was there from day one with the total understanding of the building and its own design journey, and this was fully understood and appreciated by the architects.

“LDPi had a complete free hand and the architect and client agreed with every step made through the design process. Through workshops in Perth, Oman, and Edinburgh, the seniors of both practices closely worked through all elements, speaking the same language.

“By understanding the architecture, and the architectural story, the lighting follows the architectural order, wording, and punctuation in absolute harmony.”

This harmony meant that the lighting designers did not experience any structural constraints or issues on the project, although Nisbet adds that the biggest challenge came in illuminating the 150-metre-long timeline gallery with a single source solution. “A custom-made solution by iGuzzini, using stretch fabric, was ultimately used to ensure visual continuity and stability. The single linear narrative adds to the strong architectural geometry and enhances perspective, irrespective of an excellent downward illumination provision.”

LDPi worked with iGuzzini and Louis Poulsen on the lighting for the museum, and Nisbet adds that “performance and the ability to support the highly motivated design teams of LDPi and Cox” were the main decisions behind working with these brands.

“We invited both iGuzzini and Louis Poulsen to be part of the process and allowed full engagement with ourselves and the architects,” he adds. “The level of detail was extensive with, for example, the special engraved patternation designed by LDPi applied onto the glass of all in-ground luminaires. In daytime, the luminaires morph into beautiful architectural details themselves. Such attention to detail sets the scene of care and quality throughout.”

Following the opening of the museum earlier this year, Nisbet is effusive in his praise of the project, “This is a statement piece of legacy architecture, our view and that of the architects is that the space and form is timeless and intended to be meaningful over generations,” he says.

Despite a lengthy timeline of nearly 10 years to complete, with work beginning in 2014, he adds that the project was “an absolute pleasure from start to finish, as all parties believed in the strength of the design and the legacy aspect of such a work”.

He concludes: “It was a joy to work with some of the best architects in the world who care so much; a joy to work with people within lighting manufacturers that hold the same design integrity and who similarly care.

“This was an amazing design experience, design education, and design journey for all involved at LDPi. This was about much more than a commercial project. We are privileged to have worked on this project with amazing people in an amazing country. All involved have become firm friends throughout this journey; surely what great collaboration and great design is all about.”

Winners of 2022/23 Jonathan Speirs Scholarship Fund announced

(UK) – The winners of the 2022/23 Jonathan Speirs Scholarship Fund (JSSF) – a UK-registered charity that provides support to students of architecture who wish to enter the architectural lighting design profession – have been announced.

Edward Turner of the Royal College of Art London, and Samuel Walker of Coventry University were announced by Trustees as the joint recipients in this, the final year of the awards programme.

This year’s programme also saw three commendations, which were given to Chen Weiting of the Bartlett School of Architecture, Jade Atkins of Northumbria Univeristy, and Jingwen Song of the University of Michigan.

The first award winner, Edward Turner, is studying for an MA in Architecture at the Royal College of Art, London. Through his studies, he has consistently engaged in the manipulation of natural light at both urban and interior scales, having had a longstanding fascination with the theatrical nature of architecture.

More recently, his attention turned to artificial lighting with his project Batteries Not Included, a reimagination of the Blackpool Illuminations that takes an inventive and critical approach on the use of energy and lighting, generating, and storing the electricity through kinetic structures and kinetic architecture.

The scholarship will be used to support Turner in starting his own spatial design practice, where he hopes to further explore design of a more provisional nature that encourages adaptation; and supports ways of behaving that are more in line with addressing the climatic situation we find ourselves in today.

Samuel Walker is studying architecture at Coventry University. Passionate about light since secondary school, and a self-confessed near obsessive regarding sustainability, Walker has a particular interest in the topic of light pollution. His work explores how celebrating darkness is crucial to tackling this issue, both environmentally and economically, while designs that employ subtle lighting and use contrast to shape space and experience still enable us to deliver the positive emotional and social impact that light can bring.

Currently interning at dpa lighting consultants, the scholarship will be used to support Walker in his ambition to work with professionals in the industry to set up a platform that aims to educate, inspire, and motivate students, designers, and anyone else that is interested in design, astronomy, and sustainability around the topic of lighting, and the benefits that designing well-lit spaces can have on our health and the planet.

Reflecting on the work of the scholarship, John Roake, Chairman of the JSSF, commented: “I wish to extend my congratulations to Edward Turner and Samuel Walker, who join a small but select group of scholars. Also to Chen Weiting, Jade Atkins and Jingwen Song on receiving commendations. We wish you all bright careers and trust you will always remember being touched by Jonathan’s legacy.

“When the Jonathan Speirs Scholarship Fund was launched in 2012, we pledged that we would award at least one scholarship to a student of architecture per year for 10 years. We find it hard to believe that we have now reached that point. Our mission was to assist students in their studies and follow their passion for light, just as Jonathan did.

“Over the past decade we are very proud to have awarded 16 full scholarships and helped an additional five students with commendation awards.

“We would not have been able to do any of this without the outstanding support of many individuals and organisations who have been consistently generous with their donations over the years. It has been a testament to the respect that Jonathan had within the lighting community that we have been able to find these scholarships. Our special thanks not only to our ‘Benefactors’: Designed Architectural Lighting, Hoare Lea, iGuzzini, Lightology, Lucifer Lighting, Stoane Lighting, Philips Lighting and Sean O’Connor Lighting, but also to everyone who provided financial support, both large and small.

“A massive thank you also needs to be extended to our Trustees – Mark Major, Paul Gregory, and David Speirs, without whom the scholarship would never have happened. They have given generously of their time to help nurture and develop the JSSF over the last decade.

“It has been an honour to have been chairman to a charity inspired by a great friend who is still much missed. Whilst Mark, Paul, David and I have had a lot of fun and a few heated discussions along the way, we hope we have helped many students fulfil their dreams, which is what we set out to do.”

Cariboni Group - Spoon

Spoon is the new urban lighting system designed for Cariboni by Atelier(s) Alfonso Femia.

The project stems from a lucid and severe reflection: the outdoor lamp is an object for too long relegated to a hyper-technological dimension or filled with pseudo-classicisms. In defining urban comfort, it is necessary to synchronise lighting with contemporary scenarios. For this reason, the new line of products defines urban lamps capable of communicating and reacting to changing situations, not indifferent objects, but objects integrated and coherent with the rewriting of cities.

Spoon contributes to urban design with a strong chromatic and material personality and an unprecedented project choice, particularly for an outdoor system: the volumes of the bodies are developed on asymmetrical geometries. The challenge was to design a dynamic element that can be adapted to different scales, geometries and positions between the specific space and the overall environment.

From Cariboni’s collaboration with the studio, three urban lamps of different sizes were born, which can be fixed on tall and sharp vertical rods, on low cylindrical stems, or on the wall. The different shape ratio, the possibility of positioning them at variable heights and in different orientations, define their character and luminous "nature".

The system is designed to offer maximum comfort and maximum efficiency both for horizontal and vertical surfaces. Numerous optical distributions are available for each lamp both for street and architectural lighting.

According to Alfonso Femia: “the Spoon collection moulds and makes the shapes that build space changeable. It talks about creativity, research and planning, combining shapes, functions and material relationships".

25th Hong Kong International Lighting Fair draws 62,000 visitors

(China) – Held concurrently alongside the Hong Kong International Outdoor and Tech Light Expo and the Eco Expo Asia, the 25th Hong Kong International Lighting Fair (Autumn Edition), welcomed more than 62,000 visitors from across 145 countries and regions.

Sophia Chong, Deputy Executive Director of organisers the Hong Kong Trade Development Council (HKTDC), said immediately following the event that the combined fairs had “created a cross-industry sourcing platform for global buyers, successfully leveraging synergy and attracting some 62,000 buyers collectively.”

The number of buyers from key markets reportedly grew strongly, including those from ASEAN countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand, as well as the UAE, Korea, India and Mainland China.

Running under the theme of “Light Up Every Opportunity”, the Hong Kong International Lighting Fair and International Outdoor and Tech Light Expo showcased a wide range of lighting products with innovative designs, sustainable development, and smart elements. Debuting this year was the Connected Lighting Zone, which featured more than 20 companies and brands, as well as the Connected Lighting Forum, where experts shared information and trends on smart lighting solutions.

An independent survey institute interviewed nearly 770 exhibitors and buyers at the event, finding an optimistic outlook from those surveyed. More than 67% of those questioned expect overall sales to continue growing in the next two years, with 32% expecting sales to remain unchanged and just 1% anticipating a potential decline. For traditional markets, respondents were mainly optimistic about Australia and the Pacific Islands (67%) and Taiwan (63%). Among emerging markets, the industry was primarily positive on Latin America (71%), Centra & Eastern Europe (68%), the Middle East (66%) and ASEAN countries (65%).

Smart cities and smart homes were among the technological development trends under the spotlight. As Internet of Things (IoT) applications grow in popularity, most respondents (74%) believed the smart-lighting market had great potential in the next two years. Areas with the most potential included home automation and smart-lighting control systems (47%), followed by wireless lighting control systems (33%), energy-saving lighting control solutions (30%) and outdoor smart security lighting systems (26%).

Continuing, Chong added that she was “confident that the HKTDC would continue to promote local and international trade development, bringing more business opportunities and cooperation to the industry.”

Luxconex - SR Blaze

SR Blaze is a high-quality linear light designed and built for longevity. Packed with a humidity stabiliser and advanced voltage regulation technology, it ensures consistent performance in high humidity and voltage fluctuation environments. The deep recessed lens with customised honeycomb controls glares effectively, enhancing comfort. Its slim end cap adds to the elegant aesthetics of the finish. It guarantees uniform lighting with no dark spots at butt-joints, ensuring a seamless application. SR Blaze is the epitome of performance, style, and adaptability for diverse lighting needs.

Fetzer Institute Administration Building, USA

A renovation of the Fetzer Institute’s Administration building saw lighting, designed by SmithGroup, play a key role in creating the feeling of “lightness within”.

The Fetzer Institute was founded by broadcast pioneer and former owner of the Detroit Tigers baseball team, John E. Fetzer, with the goal of “helping build the spiritual foundation of a loving world”.

Combining science and spirituality, the institute was established to support work designed to discover and enhance the integral relationships of the physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual dimensions of experience that foster human growth, action, and responsible improvement of the human and cosmic condition.

Last year, the non-profit institute underwent a renovation of its existing, triangular-shaped administration building. In keeping with the group’s wider philosophy, the goal for the renovation was to create an environment that would encourage dialogue in support of its mission, create a memorable experience, and reconfigure for growth.

Using the building’s unique footprint and vision, designers at SmithGroup, who led both the architectural and lighting design of the renovation, sought to implement inspiring spaces, including a central gathering space that harnesses “distinctive geometry and lighting elements” to evoke ancient, tent-like structures.

Paul Urbanek, Vice President and Design Director at SmithGroup, tells arc: “This renovation is about ordering a new plan within the equilateral triangular footprint of an existing Administration building that speaks to the Fetzer Institute’s mission of supporting a holistic, loving world with open dialogue.”

Paige Donnell, Associate Lighting Designer at SmithGroup, adds: “Our multi-faceted design team worked together to charette the over-arching concepts and ideas that we wished to implement, driven by the client’s goals.”

In support of these goals, SmithGroup developed a lighting concept, titled “Revealing Legacy”, which Donnell says “empowers and enforces notions of inclusivity, awareness, and open dialogue by highlighting the warmth and texture of materiality and seamlessly integrating concealed lighting treatments within architectural forms”. Within this, the design parti looked to create a sensation of “lightness within” – a challenge in itself in a space devoid of natural light.

“We needed to craft a bespoke solution that not only performed similar to daylight – diffuse, ambient, soft illumination – but also created the visual sensation of daylight effortlessly pouring through translucent materials and crafting the human experience by creating a captivating and welcoming environment for gathering.”

Central to the renovation of the Administration Building, at the heart of its angular shape, is the Convening Room, a major sacred space within the Institute. About this are a series of supporting spaces that continue the open dialogue cherished within the organisation.

Urbanek explains how the triangular form of the building impacted the rooms within, and the lighting therein: “The unique shape of the building plan made for some unusually shaped rooms. Instead of rectangles, we were confronted with parallelograms and triangular spaces. Therefore, the application of standard lighting fixtures took on a creative slant. Even the straight corridors have special attention at the corners, because they are 120°, instead of 90°.

“The major Convening Room employed a myriad of triangular forms to create a tentlike structure that incorporated the lighting. Other rooms used regular treatments placed in juxtaposition with the angled geometries.”

The triangular forms in the Convening Room are comprised of a series of custom designed and fabricated, edge-lit acrylic panels that diffuse light from an LED source concealed in the ceiling. Meticulously detailed with limited space, the 16ft acrylic features, designed with knife-edge end conditions and z-clipped backer plates, effortlessly slide into the bespoke ceiling without visible fasteners.

SmithGroup worked on numerous mock-ups with the manufacturer to fabricate a distinctive, 3D-printed acrylic refraction pattern for uniform and effective transmission of light from top to bottom. The product was reviewed at multiple scales, with appearance, ease of maintenance, and accessibility as critical design drivers. With a CCT source of 3500K, the designers at SmithGroup believe that the feature strategically contrasts a cool daylit impression and warm material palette, evoking the sensation of daylight emerging through a tent-like form, amplified by the dynamic spiral play of veiling, and revealing illuminated panels.

Donnell recalls the design process for this unique feature: “Paul and I initially sat down together one afternoon with a napkin sketch of an idea to create this structure that emits light almost magically, without visible fasteners, and fully integrated into a custom millwork triangular shaped form. We wanted to both highlight and honour the angular architecture, while also crafting an experience that was inviting and encouraging of open community dialogue.

“We talked through the initial limitations – ceiling space, fabrication methods, achieved light levels, accessibility – and we determined the only way to achieve this aesthetic and function was to find a product that was small-scale, custom-sized, and edge-lit with uniform distribution.”

Elsewhere, a newly added exhibit space showcases the owner’s legacy, highlighting key storytelling features with a playful spin. Baffled adjustable track lighting, detailed into a reveal in the ceiling and situated within an extremely low plenum space, allows for spatial adaptability. RGBW cove lighting central to the space breaks the horizontal ceiling plane and continues to evoke the sensation of “lightness within”, while custom 3D-printed patterned metal partitions filter and extend daylight from the surrounding existing building, creating a playful and comfortable expression of natural light within the windowless interior.

Office support spaces, such as huddle rooms and a library, utilise glare-free perimeter indirect solutions for visual comfort and warmth; accessible restrooms exemplify how multiple layers of indirect illumination transform the elegance and intimacy of an occupant’s experience. “We created a custom control element at the door handle that visually notifies occupants of the room’s vacancy,” Donnell adds. “This custom millwork-integrated light illuminates green or red to enforce more ‘quiet’ methods for communication of everyday tasks, that in-turn allows more space for intentional conversation.”

Donnell explains how the overarching design concept of “lightness within” extends to the various spaces within the building: “The design philosophy encouraged achievement in our somewhat competing goals, by creating a juxtaposition of dark-toned intrigue, intimacy, and comfort, with a simultaneous feeling of lightness, awareness, and limitless bounds. We capitalised on indirect illumination strategies, paired with a warm material palette to both create that welcoming environment and express the sensation of vast openness and discovery.”

Alongside this, Donnell adds that the use of indirect lighting throughout limits contrast and visual discomfort and enhances the warmth and texture of the wood materials in an effort to “create elegant, intimate, and welcoming experiences that support and inspire open community dialogue.”

While the concept of designing lighting in a completely windowless environment may seem like one of the biggest challenges that a lighting designer can face, Donnell believes that there was another, more troublesome factor to consider. “Our biggest challenge was the design, execution, and installation of our customised feature ceiling element during a global pandemic,” she says.

“Throughout the mock-up phase of the project, we needed to review varied scales of custom 3D-printed acrylic refraction patterns both quickly and effectively. This led to countless video calls with the lighting manufacturer, an abundance of shipped material samples, and innovative methods for quantifying light level performance data for the design team to validate the system in their 3D models. Once the mock-ups became larger in scale, we benefitted from teaming with a local manufacturer, and were able to drive to the factory to review intricate details in-person, wearing masks and maintaining distance.

“During the construction phase of the project, we ran into unforeseen issues with in-field humidity conditions causing our custom panel elements to bow with the heat. Fortunately, we had a great team of designers, contractors, and fabricators, who were remotely able to verbally and visually communicate challenges and concerns to find novel solutions to these unprecedented site challenges.”

Urbanek adds that the logistics of remodelling within an existing building and framework brought with it some further struggles. He says: “As this was a remodel of an existing building, we tried hard not to disrupt the structure, but rather work within. Wherever possible we incorporated the existing columns into the design.

“The main Convening Room was placed in the centre of the plan, in the largest open space available, and its truncated hexagonal plan is a result of trying to gain the most area within the structure. The Fetzer Exhibit space is designed as a rhombus shape for many of the same reasons. In both of these spaces, working around the mechanical ducts and structural beams to achieve greater ceiling height was tricky.”

That being said, on reflection the design team at SmithGroup, as well as the client, are all “extremely satisfied” with the outcome of the project. Donnell adds: “Photos can’t fully describe the experience of this technically static system, with a seemingly dynamic effect. The sensation of moving about the space and experiencing the perspective-driven environment and its revealing panels is difficult to describe but it is immensely felt by the inhabitants.”

Both Donnell and Urbanek also feel that the new lighting design is integral to the ambience of the renovation, and particularly in achieving the goal of “lightness within”.

Urbanek comments: “Lighting is a key element of the renovation. The built-in fixtures of the Convening Room add to its tent-like form and act as almost skylights to the most internal room in the building. The mystery of an evenly lit space where one can only view half of the light fixtures from any point adds to the spiritual nature of the space. It is intended to bring a sacred feeling to those within. The exhibit space again is lit in a fashion to highlight within the exhibits, creating a rich visual environment.”

Donnell adds: “I believe the power of lighting and its intentional interaction with form can sometimes be undervalued. With this project, however, lighting was fundamental to the design process, which ultimately made the project much more successful. The design philosophy of ‘Lightness Within’ allowed us to challenge the norm, expand our impact, and truly design holistically to create a one-of-a-kind experience, curated for our client’s specific needs.”

Perhaps the highest praise for the renovation though, comes directly from the client. Rob Lehman, Fetzer Trustee, says of the new-look space: “The new expression of the Administration Building – the Commons, One World Room, and all the other carefully designed meeting spaces – has been created with such a sense of the sacred. These spaces represent a deepening of our relationship-centred work.

“Standing in the Exhibit Room and reflecting on our history made me realise how the remodelling is truly an ‘outward visible sign of an inward invisible reality’.”

VK Leading Light - Akrovatis

Born by VK Leading Light

Light and Human

Symmetry - Balance - Light

Akrovatis' movements delicately interplay with light and shadow and transform it into a game of communication with human.

VK/04491/PE/B/W

Kelvin 3000K | Power 5W+15W | Lumen 350lm+533lm | Voltage 220-240V

The Point of No Return

Can the lighting profession survive the new public awareness of the problems of light pollution? Dr. Karolina M. Zielinksa-Dabkowska investigates.

This article reviews various recent publications and initiatives to extend our understanding about the impact of light pollution on the natural world, human health, flora, fauna, and the night sky. Consequently, it’s clear an immediate change in design practice of the lighting profession is required because new approaches for external illumination are generally worsening lighting conditions instead of improving.

Based on recent research, light pollution has increased annually by almost 10%, prohibiting visibility of stars in the night sky [1]. When this statistic is compared with other findings from 2016, and the estimates made then of 2% - there’s a significant increase [2]. Unfortunately, this type of pollution has generally not been considered a threat by regulatory bodies, local and regional decision makers. However, this attitude has started to slowly change more recently.

To better understand the overall impact of this type of pollution on biodiversity, in December 2022, the European Commission announced a research call under Horizon Europe Framework Programme in order to monitor and mitigate its adverse effects on the conservation status of species and habitats affected. It was titled “Impact of light and noise pollution on biodiversity” [3], and €7m will be awarded to two project teams – one covering terrestrial (both urban and rural areas), and the other aquatic (fresh water and marine environments). These two projects will start in January 2024, and they will last four years. Based on their outcomes, European Parliament will introduce the necessary regulations. The consortium partners building these two teams will be officially announced in autumn. The results of the project are expected to contribute to the following outcomes:

• The impact of light pollution on biodiversity and ecosystem services is better understood, and nature restoration activities, as planned in the EU biodiversity strategy for 2030, are supported.

• Private and public stakeholders become more aware of the impacts of light on biodiversity.

• Specific measures are developed to assess, prevent and mitigate the negative impacts from light on biodiversity.

• Networking capacity is built around the impacts of light on biodiversity.

Then in June this year, the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in the special section of their peer-reviewed academic journal Science Magazine, called “Light Pollution”, published review articles and a policy forum [4]. This recent issue confirmed the gravity and relevance of the topic, as this weekly journal publishes top research themes from around the world.

In the “Measuring and monitoring light pollution: Current approaches and challenges” publication, researchers investigated measuring and monitoring methods of artificial light at night (ALAN) both from the ground (including single-channel photometers, all-sky cameras, and drones), and through remote sensing by satellites in Earth’s orbit. Moreover, the authors identified several shortcomings and challenges in current measurement approaches [5]. Another review, called “Effects of anthropogenic light on species and ecosystems”, discussed the impact of man-made light on mammals, amphibians, reptiles, fish, and plants, and how solutions and new technologies could minimise these negative ecological effects [6].

Adverse aspects of outdoor lighting on human health were discussed in “Reducing nighttime light exposure in the urban environment to benefit human health and society”. This covered impacts such as eye strain, stress to the visual system, circadian desynchrony, sleep disruption and suppression of melatonin secretion, and included the increased risk of developing chronic diseases. Moreover, critical areas for future research were identified, and recent policy steps and recommendations were introduced for mitigating light pollution in the urban environment [7].

The topic of the impact of artificial light at night, radio interference, and the deployment of satellite constellations were also analysed in “The increased effects of light pollution on professional and amateur astronomy” [8]. Lastly, an article in the policy forum called “Regulating light pollution: More than just the night sky” examined the hard and soft laws connected to light pollution in the European Union, France, Korea and the UK [9].

Most notably, the cover of this magazine featured a wild little penguin silhouetted against the brightly illuminated city of Melbourne.

On the 12 July, 2023, the European Parliament passed a new nature restoration law [10] to boost biodiversity and climate action, and terms such as “light pollution” and “artificial lighting” were used throughout this document [11].

Moreover, earlier this year, the House of Lords Science and Technology Committee of the UK Parliament conducted an oral public inquiry into the effects of artificial light and noise on human health [12]. In the published report, the committee reported evidence for claims made about the effects of artificial light on human health, the inadequacy of the existing policy and regulatory framework for addressing light pollution in the UK, and options for reform to address any harmful effects that were identified [13]. Based on all the information provided, the committee confirmed that light pollution is “poorly understood and poorly regulated”. Representatives of the lighting profession were present as witnesses: Guy Harding, Technical Manager from the Institution of Lighting Professionals; Allan Howard, Past-President of the Institution of Lighting Professionals; Stuart Morton, Professional Head of Highways and Aviation Electrical Design at Jacobs; Andrew Bissell, President of the Society of Light and Lighting.

The Way Forward

In the past, misinformation on various lighting related topics has been spread by many companies. A good example is the “ban the bulb” initiative where, for example, lamp manufacturers tried to convince lighting professionals and the general public that compact fluorescent lamps (CFLs) were the best light sources to be used due to their energy savings, instead of the old-fashioned General Lighting Service (GLS) incandescent lamp. Not only that, but they were also falsely promoted as healthy and environmentally conscious. We know now the folly of those claims, as the lamps contained harmful mercury in liquid and gas form, and there was also no proper process for recycling. The same could be said about the ban of incandescent sources for LEDs. We now know that many people cannot tolerate LED lighting technology, and yet, we’ve gone ahead with the banning of this safe and side effect-free light source, without anything else comparable to take its place.

In order to understand the current situation on light pollution, objective unbiased research is therefore necessary, so we can act and apply this new knowledge in our lighting projects. In order to do so, a few steps are required: quantifying the effects of light pollution has to be established first, then specific lighting level targets need to be set, and it should be a priority to create a framework for regulations. Applying the ROLAN manifesto in lighting projects can be a starting point to minimise the impact of the polluting effects of LED lighting technology. Another way to learn about this important topic and be informed about responsible outdoor lighting, and how to apply it in day-to day lighting practice, is to watch recordings from the inaugural ROLAN conference [14]. These recordings connect both research and practice, and they are provided free of charge. This work utilises the immense depth of knowledge, expertise, and innovation that currently exists, in order to broaden horizons, increase understanding, and improve communication on the topic of light pollution. The ultimate aim is to facilitate much-needed collaboration and support to improve lighting practice, and to also enhance research, as well as networking opportunities between researchers, practitioners and manufacturers in order to enable responsible illumination in our towns and cities.

References

1. C. C. M. Kyba, Y. Ö. Altıntaş, C. E. Walker, M. Newhouse, Citizen scientists report global rapid reductions in the visibility of stars from 2011 to 2022. Science 379, 265–268 (2023).

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abq7781

2. F. Falchi, P. Cinzano, D. Duriscoe, C. C. M. Kyba, C. D. Elvidge, K. Baugh, B. A. Portnov, N. A. Rybnikova, R. Furgoni, The new world atlas of artificial night sky brightness. Sci. Adv. 2, e1600377 (2016).

https://www.science.org/doi/epdf/10.1126/sciadv.1600377

3. Impact of light and noise pollution on biodiversity. Available online:

https://ec.europa.eu/info/funding-tenders/opportunities/portal/screen/opportunities/topic-details/horizon-cl6-2023-biodiv-01-2 (accessed on 31 July 2023).

4. K. T. Smith et al. Losing the darkness. Science 380,1116-1117 (2023).

https://www.science.org/doi/epdf/10.1126/science.adi4552

5. M.Kocifaj et al. Measuring and monitoring light pollution: Current approaches and challenges. Science 380,1121-1124 (2023).

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adg0473

6. A.K. Jägerbrand, K. Spoelstra, Effects of anthropogenic light on species and ecosystems. Science 380, 1125-1130 (2023).

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adg3173

7. K. M. Zielinska-Dabkowska et al. Reducing nighttime light exposure in the urban environment to benefit human health and society. Science 380, 1130-1135 (2023).

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adg5277

8. A. M. Varela Perez. The increasing effects of light pollution on professional and amateur astronomy. Science 380,1136-1140 (2023).

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adg0269

9. M. Morgan-Taylor, Regulating light pollution: More than just the night sky. Science 380, 1118-1120 (2023).

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adh7723

10. New Nature Restoration Law boosts biodiversity and climate action across Europe. Available online:

https://cinea.ec.europa.eu/news-events/news/new-nature-restoration-law-boosts-biodiversity-and-climate-action-across-europe-2023-07-12_en (accessed on 31 July 2023).

11. Nature Restoration Law. Available online:

https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/nature-and-biodiversity/nature-restoration-law_en (accessed on 31 July 2023).

12. Call for Evidence. Available online:

https://committees.parliament.uk/call-for-evidence/3032 (accessed on 31 July 2023).

13. Light and noise pollution are “neglected pollutants” in need of renewed focus. Available online:

https://committees.parliament.uk/committee/193/science-and-technology-committee-lords/news/196536/light-and-noise-pollution-report-publication/ (accessed on 31 July 2023).

14. ROLAN 22 Video Access – Registration. Available online:

https://www.cibse.org/get-involved/societies/society-of-light-and-lighting-sll/sll-events/rolan-22-video-access-registration (accessed on 31 July 2023).