Call for submissions for [d]arc thoughts at [d]arc room pop-up

(UK) – [d]arc room pop-up @ Design London, brought to you by [d]arc media, opens call for submissions for its [d]arc thoughts talks programme.

Moderated by [d]arc media’s team of editors, [d]arc thoughts will run from 22 – 24 September and feature insightful discussions from leading industry professionals working with light.

If you would like to be considered for inclusion on a [d]arc thoughts panel, get in touch here, outlining your areas of interest and expertise.

Recognising London’s profound influence over Architecture and Design specification, [d]arc room pop-up @ Design London is a new and enhanced event experience underpinned by the wealth of knowledge of both [d]arc media and Media 10, organisers of Design London.

[d]arc room pop-up @ Design London will feature a highly curated selection of lighting brands, talks programme and light-art installations, providing a unique platform to meet with leading lighting designers, architects, interior designers, developers and retailers at what will be the must-attend event during London Design Festival.

The UK has the second largest design industry in the world and is the largest in Europe. London has seen design-led businesses more than double since 2010.

Of the 25,000+ visitors to Design London (100% Design) in 2019, 80% were architects or designers with over 50% interested in lighting specification.

Of the 217 lighting design practices in the UK, over half (116) are located in the Greater London area (source ILDS 2021). This is by far the biggest concentration of lighting designers in one city in the world.

Situated alongside [d]arc room and Design London, Greenwich Peninsula will welcome London’s first purpose-built Design District – a collection of sixteen buildings designed by eight architects that will house 1,800 creatives. A new type of London is being developed specifically for the creative community. A mixture of architectural voices, open house workshops and design lovers will create an undeniable buzz of activity during London Design Festival aligning with [d]arc room and Design London’s celebration of the capital’s thriving design scene.

www.darcroom.com/call-for-speakers

Newly launched Workspace Design Show to hold workspace lighting webinar on 7 July

(UK) – As part of the build-up to the first ever Workspace Design Show, to be held on 4-5 November at London’s Business Design Centre, event organisers are holding a series of design webinars.

The Spotlight Series covers various aspects of workspace design, such as sustainability, product design and lighting design.

The third instalment of the Spotlight Series, entitled ‘Light Your Space’, will be held on 7 July, and will discuss how lighting design can help to create effective and enjoyable workspaces.

Panelists for this session, which will be chaired by arc’s Matt Waring, include: Paul Nulty, Founder of Nulty lighting, Neale Smith, Director at Foundry Lighting, and Susan Lake, Design Director at Susan Lake Lighting Design.

Registration for the session is free – more information on how to register can be found here.

Alongside the Spotlight Series of talks in the lead up to the event, organisers of the Workspace Design Show are very excited about the top level experts and partners involved in the show. During the event, a series of Workspace Design Talks will include a host of well-respected voices from end-user clients, including: Robert McLean, Head of Real Estate & Design at PwC; Emily Harding, Workspace Design & Culture Lead at Aviva; and Alan Bainbridge, Head of Workplace and Corporate Real Estate at BBC.

International Furniture-led consultancy, The Furniture Practice, will be showcasing the latest high-end furnishings available from world-class brands such as Vitra, Gubi, Brunner and Andreu World, to create a stunning environment for the conference talks at the show.

Other brands on display at the Show include Buzzispace, Actiu, Dams Furniture, TC Office Group, Abstracta, Interface, Camira Fabrics, Mute, Kettal and IOC Project Partners.

Registration for the show will open in July. Those interested in attending can register interest to receive advanced notice on the limited number of free passes for trade visitors here.

Sirius Lighting Office takes home Radiance Award at 38th Annual IALD Awards

(Worldwide) – Returning online for the second year in a row, the winners of the 38th annual International Association of Lighting Designers (IALD) International Lighting Design Awards, presented by Cooper Lighting Solutions, were announced on Thursday 24 June.

The awards recognised 20 projects from 10 countries, spanning exteriors, interiors, memorials, hospitality, hospitals, retail, and places of worship.

Mirjam Roos, IALD Awards Chair and co-host for the awards presentation, said of this year’s awards programme: “Every year we see an increase in the quality of entries and this year is certainly no different. Our seven-member panel of judges evaluate each project submission for demonstration of excellence across 10 distinct areas in a rigorous and blind process.”

The highest point scorer across all entries, in addition to receiving an Award of Excellence, is also given the IALD Radiance Award for Excellence in Lighting Design. This year, the Radiance Award went to Sirius Lighting Office, for the Toranomon Hills Business Tower in Tokyo, Japan.

The awards winners are as follows:

IALD Radiance Award

Toranomon Hills Business Tower, Tokyo, Japan – Sirius Lighting Office

IALD Award of Excellence

Canadian Parliament West Block – Committee Rooms, Ottawa, Canada – Office for Visual Interaction (OVI)

Central Mosque, Shali, Russia – Natalya Koptseva and Vasily Tarasenko

Kungsträdgården, Stockholm, Sweden – Light Bureau

NorthConnex, Sydney, Australia – Lux Populi

IALD Award of Merit

25 E Washington Lobby, Chicago, USA – Schuler Shook

600 West Chicago Lobby Renovation, Chicago, USA – Schuler Shook

Chongqing Changshou Sales Gallery, Chongqing, China – Glint Lighting Design

CME Group, Chicago, USA – Schuler Shook

The David H. Koch Center for Cancer Care at Memorial Sloan Kettering Center, New York, USA – Licht (in-house lighting studio at ICRAVE) and HLB Lighting Design

Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial, Washington DC, USA – L’Observatoire International

Harrods Fine Dining, London, UK – Lighting Design International

Nitro, Seattle, USA – Oculus Light Studio

The Ritz-Carlton Nikko, Tochigi, Japan – Worktecht & Co

Sharjah Mosque, Sharjah, UAE – Light Concept

Starbucks Reserve Tianjin Riverside 66 Flagship, Tianjin, China – WEGO Lighting Design

Takanawa Gateway Station, Tokyo, Japan – Lighting Planners Associates

Wang Jing Memorial Hall, Songyang, China – School of Architecture, Tsinghua University and One Lighting Associates (Beijing)

IALD Special Citations

Boulevard of Arts, Dnipro, Ukraine – Expolight

K11 Art and Cultural Centre, Hong Kong – Speirs Major

The IALD praised the work of its panel of seven judges for the 2021 IALD Awards. The panel includes five IALD members at various experience levels, alongside an architect and interior designer. The judging panel was: Yahui Cheng, Kristen Garibaldi, Julia Hartmann, Vladan Paunovic, Glenn Heinmiller, Joe Lawton and Tina Turrisi.

The full awards presentation is available to view online here.

Stoane Lighting to hold virtual Park Event this Friday

(UK) – Stoane Lighting’s well-renowned annual lighting get-together is moving online this Friday.

Typically held in a sunny London park, the manufacturer was hoping to bring lighting designers together for a long overdue physical party this week, but as with many industry events over the past year, it has had to move online.

However, the move online has meant that the event has opened up to a wider, international lighting audience.

For the new, online celebration, Stoane has partnered with the GreenLight Alliance and the Society of Light and Lighting (SLL), for a series of mini workshops and discussions centred around sustainability and the post-Covid workspace. Led by Sharon Stammers and Martin Lupton of Light Collective, who will kick off and conclude the festivities, each session will also be followed by a Q&A session moderated by Emilio Hernandez, Chairman of the GreenLight Alliance.

The agenda for the event is as follows:

Block 1: The post-COVID workspace

- Occupancy management systems with lighting interventions linked to social distancing

- Wayfinding and smart space management with links to lighting

- The launch of Stoane Lighting’s VCL (Video Conferencing Light)

Block 2: Sustainability

- What we’re doing with our waste aluminium: forge and sandcasting demos

- Midton talk about recycling plastic

- ReNew in detail: repairing and remanufacturing luminaires when, what and how

- Guest presentation by the GreenLight Alliance

- Guest presentation by the Society of Light and Lighting on the forthcoming TM66 (Circular Economy Assessment Methodology)

Registration for the event is free – more information on how to register can be found here.

Acclaim Lighting Flood One EO Color

Flood One EO Color is a high output, outdoor rated, colour-changing LED floodlight with a very low-profile design. Ideal for façade and wide-area lighting applications, the outdoor RGBW LED floodlight is available in multiple variants, including Acclaim’s Spectrum Technology which allows for a more expansive colour palette and dynamic white capability. Flood One EO Color comes with a standard 10° beam angle with optional spread lenses of 20°, 40°, 70°, 90°, and 10° X 60° for custom lighting applications.

Clear Lighting Flexglo F23

Flexglo F23 reflects the trends of LED neon flex, requiring small physical size yet ideal lumen output, and comparatively more cost-effective. It may be easier to source smaller ones in the market, however hardly any can combat it in terms of appearance, colour consistency, heat dissipation, waterproof, and lifespan on average. Underpinned by Clear’s rich experience in the lighting industry, the company has reached a subtle balance to fit high-end design demand.

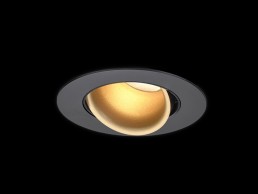

John Cullen Lighting Vorsa Dot

Bring focus to what matters with the smallest track-mounted luminaire on the market – the Vorsa Dot. With a choice of flood or spot luminaires, multiple different optics and five different snoots, it allows your lighting to be as tailored as your display. An innovative proprietary track with different mounting options offers maximum control with independent dimming levels. The Dot delivers a powerful 65Lm along with a CRI of 98.

Bright Special Lighting Regio Flex LED

The Regio Flex LED is the latest entry into Bright Special Lighting’s high-quality LED lights. The wallwasher has a smart design, allowing the fixtures to be hidden, while ensuring that walls and ceilings are properly illuminated with options of optical lens’ from 5-60. With a high pressure casting aluminium body, low wattage, IP65 rating and uniform lighting, designers can create indirect lighting effects, integrate mood lighting and bring the night to life.

LightGraphix LD792

LightGraphix has launched four new downlights - LD780, LD782, LD790, and LD792 - with single colour, two-tone, fixed and adjustable options, rated IP65 for interior, exterior and marine applications. Bezel diameters start at 46mm, achieving an excellent size to output ratio delivering over 400lm. Colour temperatures range between 2200K-5000K and beam angles include several medium and a super tight 10° narrow. A single deep recessed optic ensures ultra-low glare, superior beam shape and no multiple shadows.

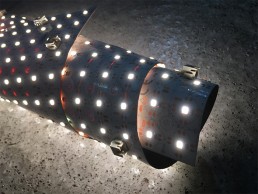

Applelec Auragami

Helping to bridge the gap for achieving complex illuminated schemes, Auragami from Applelec is an extremely flexible and versatile backlighting panel. Delivering flawless illumination to sharp edge designs, Auragami can be shaped at an impressive 90° angle or wrapped around columns and curved surfaces. Utilising tight pitch, powerful LEDs, Auragami is the ideal solution for producing luminous backlighting for particularly dense surface material of up to 20mm depths.

ewo if round

A striking join at the neck of this luminaire accommodates ewo’s A–Series optical system, opening ewo’s entire light-shaping technology toolbox for bespoke lighting configurations.

Through the if round, ewo strives to shape and target light to improve the quality of cityscapes and all manner of architecture, for every imaginable lighting design freedom.

Ligman KWH Range

A unique linear shape, rounded profile luminaire with surface-mounting bracket, and robust, tiltable body, offered in different lengths means the KWH range provides multiple optical and professional lighting solutions for building, area and façade lighting. Suitable for installation in narrow spaces, both single and twin modules can be tilted up to 180°. Complete with a remote-control gear box attached to the bracket to reduce heat from the body, it covers RGBW and RGBTW (RGB Tunable White 2700K - 6500K) systems via RDM, DMX systems.