Technilum Jeny

Singular in its style and applications, Jeny has a triangular shape profile and is equipped with three technical grooves that facilitate accessorisation. In tribute to Jenny Holzer, innovative artist in word expression, Jeny can be coupled with “LittleWords” from Technilum: an integrated LED screen allowing the interactive diffusion of messages or animations thanks to a dedicated application.

Acclaim Lighting Outdoor Link System

The IP67-rated Outdoor Link System quickly and easily links Acclaim Lighting’s Dyna Drum and Dyna Accent series fixtures, while eliminating excess hardware for lighting projects. The system allows the linking of up to 32 fixtures from a single power source without the need for a connection point at every unit. The system includes T junction, link cable, feed cable and end cap connection points, and performs in temperatures from -40°C to 80°C.

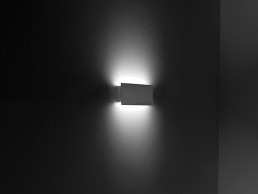

L&L Luce&Light Berica

The Berica family combines minimalist design with the practical functionality of a built-in power supply, making the double-beam, wall-mounted fixtures ideal to discreetly blend into the wall it is installed on. Available in three sizes – a 120mm square, and two rectangular options at 340mm and 620mm long – Berica offers a choice of three different styles of cover: convex, flat and concave, with a slim body starting from just 30mm. The range uses light sources with a CRI>90 for better quality, while the rectangular options are available in a dimmable version that uses the DALI protocol.

Valmont Customised Wooden Poles

Bespoke wooden light poles from Valmont Structures offer exquisite design for spaces demanding solutions that are both innovative and functional. These advanced poles bring style to any project and are customisable in heights up to 25-meters, with detailed dimensional and capacity information calculated on a per-project basis. Sustainably sourced and treated for longevity, Valmont’s light poles are as brilliant as your ideas.

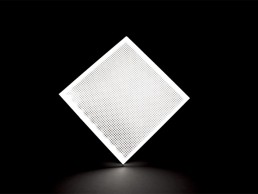

Applelec LED Light Sheet

Celebrating 15 years of its UK-manufactured LED Light Sheet, Applelec’s bespoke light panel has brought light to hospitality, retail and office space designs. The company continually modifies the engineering of its light panel, improving its capabilities and incorporating more advanced LEDs such as its new RGBW options, to consistently deliver a superior backlighting solution.

Siteco DL 50

DL 50 is a technical and decorative solution as a mast and catenary luminaire. The DL 50 LED is available not only as a mast and catenary luminaire but also comes in two sizes. Different lumen packages and three light colours provide additional flexibility in application. HD faceted reflectors ensure precise light control and glare-free lighting.

LightGraphix Light Engines

New light engines are now available across LightGraphix high-power LED products delivering up to 900lm, beam angles between 10° to 65°and colour temperatures of 2200K to 5000K. Data sheets have had a complete refresh, with added performance data including UGR, LOR, TM30, peak intensity ratings and lifetime values set at an industry leading L90B5 at 90,000hrs. Toughened, black trim glass and new in-house paint finishes will enhance the existing high quality machined bezels.

Hacel Explora Star

The Explora Star LED luminaire is an artistic choice for producing a unique lighting statement. As part of the Explora Range, the Explora Star showcases a translucent yet reflective design, offering direct and indirect lighting. The luminaire can be easily linked to create an array of imaginative configurations, delivering up to 5,460 lumens and efficacies of up to 88 lm/W. Complementary pendants and colour changing options complete the range.

IALD launches new Eastern Canada Chapter

(Canada) – IALD Eastern Canada Chapter joins more than 30 Regions + Chapters worldwide.

The IALD has announced the addition of the IALD Eastern Canada Chapter to its growing network of IALD Regions + Chapters across the world.

These chapters give the association’s 1,500 lighting design members the ability to connect and create meaningful programming for local professionals passionate about lighting, including lighting designers, architects, interior designers, lighting manufacturers and more. The latest chapter joins more than 30 active Regions + Chapters around the world.

“With this new chapter in Eastern Canada, we are looking to build a bridge between lighting designers and all the different professionals in the design industry, and increase awareness of the lighting design profession,” said Alicia Davila Monterrey.

IALD coordinator Sophie Charvein added: “We are looking forward to promoting lighting designers as essential partners to improve projects in the built-environment. This chapter will be a great way to build connections and strengthen relationships with our fellow lighting designers, and also with the professionals that we interact with on projects.”

Wästberg announces investment by XAL

(Sweden) – New partnership signifies a major step forward for Swedish lighting brand.

Wästberg, the Swedish lighting company founded by Magnus Wästberg in 2008, has announced a new partnership with Austrian lighting specialists XAL. The move will see Wästberg and XAL buy out the founding shareholders, with XAL becoming the sole minority partner in the business.

Wästberg will remain as CEO and the majority stakeholder in the business, with the company continuing to operate as an independent brand headquartered in Sweden.

The deal will also see Wästberg produce the majority of its lamps at XAL’s production facilities in Austria and Slovenia, and XAL’s sales team represent the Wästberg brand worldwide.

Magnus Wästberg said: “For some years, I have been working hard to find a way to increase the growth rate of Wästberg without losing our core values and the culture that has come to embody our long-term relationships with designers, suppliers and customers. Scale is a must to be able to make truly good lighting, to fully explore the ideas generated in our collaborations and to take advantage of all the opportunities presented by the rapid development of technology.

“The support of XAL provides the perfect partnership for the next chapter in the evolution of Wästberg. It is a partnership where we will continue to have the core values and culture of a family-run company coupled with the resources of a big one.”

Paul Fraissler, Director of International Sales at XAL, added: “We complement each other perfectly. On top of XAL’s high-end architectural lighting solutions and Wever & Ducré’s decorative luminaires, we are now offering our customers designer lighting by the world’s most renowned architects, designers and lighting experts. Furthermore, we are strengthening our position in the Scandinavian market and our international sales team is distributing Wästberg’s high-end designer luminaires throughout Europe.”

ILP to resume How To Be Brilliant sessions

(UK) – Support sessions return for lighting students as ILP How To Be Brilliant team announces partnership with Bega.

The Institution of Lighting Professionals (ILP) has announced plans for the return of its How To Be Brilliant series – designed to attract students, interns, apprentices and new entrants to the lighting profession.

The How To Be Brilliant initiative seeks to connect the lighting community, giving junior members of the industry the chance to connect with an inspiring expert who will talk about lighting in a way that formal education doesn’t necessarily cover. The 2021 series of fun and friendly, digital CPD events has been sponsored by Bega.

The first session will be How To Be Brilliant at Telling Stories With Light, given by lighting designer David Gilbey, Founder of d-lighting, on 1 March at 13:00 GMT.

Michael Wilson, Bega UK Managing Director, commented: “We are thrilled and proud to become a part of the How To Be Brilliant team. The work the ILP does to support and inspire new generations of lighting designers is important to the whole industry, and aligns with the Bega ethos and dedication to long-term sustainable practices. Our commitment to How To Be Brilliant strengthens our relationship with the Institution as a Premier member, and builds on the volunteering experience our staff have within the ILP community.”

Jess Gallacher of the ILP added: “How To Be Brilliant is a wonderful way for our charity to share knowledge about better lighting and nurture career development. The initiative started in 2014 and over the years, we have helped students blossom and become established in successful careers. It’s great news that we can now bring back and continue this work despite the effects of the pandemic, with online sessions including CPD talks and networking. We are delighted to have the support of Bega in bringing the lighting community together in a friendly and supportive way.”

To find out more and to book to attend, visit www.theilp.org.uk/brilliant, or contact jess@theilp.org.uk

Ruth Kelly Waskett named SLL President-Elect

(UK) – Kelly Waskett to take over as SLL President in May 2021.

The Society of Light and Lighting (SLL) has announced Ruth Kelly Waskett as President Elect. She will take over from current president Bob Bohannon in May 2021.

Kelly Waskett is an Associate at Hoare Lea, and has a rich background in engineering, lighting design and academia. She is dedicated to showcasing how daylight can bring buildings to life and the positive impact that it has on our health and wellbeing.

She has sat as Vice President of SLL for the past four years, and as President, she hopes to lead the Society as it aims to tackle challenges within the industry, highlight the importance of a well-rounded perspective, and promote how light and daylight can be used as an integrated tool.

She said: “I’m honoured and excited to be taking up the role of SLL President this year. I’m really looking forward to playing a part in spreading the message about the power of light in making us healthier and happier.”

www.sll.org.uk

www.hoarelea.com